Glitter & Greed: How Two Cousins Conned Tiffany's and Built America's Fake Diamond Empire

In 1872, a Kentucky grifter and his cousin sold a worthless patch of dirt to the titans of Wall Street. The secret ingredient wasn't diamonds—it was pure, unadulterated Gilded Age hype.

In the summer of 1872, the richest men on the West Coast were sitting on the secret of the century. In a city built on the frenzy of the Gold Rush, this new discovery was whispered to be even bigger. It wasn’t just another vein of silver or a flash in the pan. It was diamonds. A massive, world-changing field of them, discovered right in the American West.

The news came from two seemingly ordinary prospectors, Philip Arnold and John Slack, a pair of Kentucky cousins who played their part to perfection. They were weathered, soft-spoken, and appeared utterly overwhelmed by the magnitude of their find, which, as it turns out, is a fantastic way to disarm men who are used to cutting deals with sharks. They convinced a syndicate of Gilded Age titans, including the ambitious founder of the Bank of California, William C. Ralston, that they had stumbled upon a fortune that would rival the mines of South Africa.

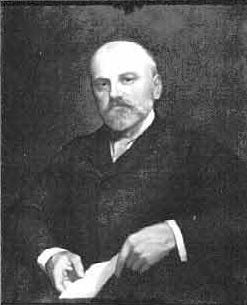

The excitement was infectious. And when the investors sent a sample of the gems to the one man whose name was synonymous with luxury, Charles Lewis Tiffany, the last shred of doubt evaporated. Tiffany, the founder of Tiffany & Co., erroneously appraised the small bag of worthless stones at a staggering $150,000. That was it. The final seal of approval. The San Francisco and New York Mining & Commercial Company was officially incorporated, capitalized at an immense $10 million, ready to control a non-existent bonanza.

It was a perfect plan, a license to print money backed by the biggest names in American finance and industry.

There was, however, one small, microscopic problem.

The diamonds were fake. All of them. The entire discovery was an elaborate, brilliantly executed fraud—a worthless piece of Wyoming territory “salted” with a few thousand dollars’ worth of industrial-grade gems purchased in Europe.

This isn’t just the story of a crime. It’s a masterclass in deception and a brutal lesson in greed. It’s a story about a nation so high on its own myth of manifest destiny that it was practically begging to be conned. It’s the tale of how two good ol’ boys with a bag of rocks brought the titans of industry to their knees, and how it took a new kind of American hero - the skeptical, methodical scientist - to unravel the whole damn thing.

The Masterminds & The Marks

Every great con is a work of the theater, and this one had a hell of a cast. On one side, you had the architects of the lie, a pair of cousins who were far more clever than they let on. On the other, a syndicate of powerful men so blinded by dollar signs that they couldn’t see the truth right in front of them.

The Brains & The Beard

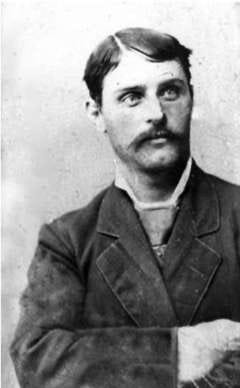

The frontman of the operation was Philip Arnold, and let’s be clear: he was no simple prospector. He was a veteran of the Mexican-American War and the California Gold Rush, a man seasoned by the harsh realities of the frontier. More importantly, he’d worked as a bookkeeper for a diamond drill company, which likely gave him both the inspiration for the scheme and access to his first batches of low-grade industrial diamonds. But his greatest asset was his performance. Investors who met him described him as serene, confident, and possessing an air of simple, disarming honesty. He looked and sounded like a man who was just smart enough to find a diamond field but too simple to lie about it. It was a masterful act.

His cousin and partner, John Slack, was the quintessential silent partner. Described as taciturn and listless, his quiet, weather-beaten presence was the perfect contrast to Arnold’s smooth talk. He was the human prop, the living embodiment of the “aw, shucks” frontier spirit that made their story so believable. Arnold was the brains; Slack was the beard. Together, they were the perfect package.

A Syndicate of the Swindled

Of course, a con only works if you have the right marks, and Arnold and Slack found a whole crew of them. These weren’t fools, but their own ambition made them vulnerable.

The biggest fish was William “Billy” Ralston, the founder of the Bank of California and arguably the most powerful financier on the West Coast. Ralston was an empire-builder, the financial engine behind the legendary Comstock Lode, a man who thought in terms of grand, visionary projects. For him, a domestic diamond mine wasn’t just a good investment; it was another jewel in the crown of his West Coast empire, a venture he bragged could be worth $50 million.

Then you had the hype man, Asbury Harpending. Harpending was a speculator and adventurer with a seriously colorful past - including a conviction for treason for trying to outfit a Confederate privateer during the Civil War. Decades later, he would write a self-serving memoir painting himself as just another innocent victim of the hoax. The historical record, however, suggests he was a key promoter who met the swindlers, hosted the dramatic gem reveal at his home, and traveled to New York to help organize the company. Innocent dupe or willing accomplice? The line gets blurry with this guy.

But the final, crucial piece of the puzzle - the man whose reputation turned a wild story into a sure thing - was Charles Lewis Tiffany. Yes, that Tiffany. The syndicate sent a sample of the gems to his prestigious New York house for an expert appraisal. His valuation of the nearly worthless stones at an astounding $150,000 was a catastrophic professional error. The blunder was likely born from a mix of inexperience with uncut diamonds and the national excitement of the discovery. In a move that screams conflict of interest, Tiffany himself even became an investor after his own appraisal. This decision would become a significant, if temporary, stain on his company’s powerful brand.

The Execution: A Masterclass in Humbug

So, how did they do it? How did two cousins from Kentucky pull off a swindle so audacious it became a legend? They followed a simple, brilliant playbook: get the props, set the stage, create a spectacle, and then get an “expert” to sign off on the lie.

The European Shopping Spree

First things first: you can’t have a diamond mine without diamonds. In the summer of 1871, using aliases, Arnold and Slack sailed to Europe on a business trip. They went to the diamond-cutting districts of London and Amsterdam not as sellers, but as buyers. They spent somewhere between $20,000 and $35,000 on their raw materials. But they weren’t buying glittering, jewelry-store gems. They were buying the scraps: uncut, rough, industrial-grade diamonds, garnets, rubies, and sapphires, all of low quality. They were the perfect props, just convincing enough to look like they’d been pulled from the earth.

Salting the Mine & Setting the Scene

With their bags full of rocks, they returned to the states and picked their stage: a remote, sun-baked mesa near the border of the Colorado and Wyoming territories. There, they “salted” the earth, scattering their European gems in a few select spots, making sure to stomp them into the dirt and stuff them into crevices to make them look like a natural deposit.

But just having a salted field wasn’t enough; they had to make the act of finding it seem epic. When the investors insisted on sending representatives to see the proof, Arnold and Slack agreed, but with a flair for the dramatic. The party was led on a deliberately confusing, four-day horseback journey from the railroad at Rawlins, Wyoming. Arnold and Slack pretended to be lost, took winding, circuitous routes, and forced the men to be blindfolded for the final, crucial miles of the trip. It was a brilliant piece of theater designed to exhaust and disorient their companions, making the location seem impossibly remote and difficult to find. In reality, they were only about 40 miles from a major railroad town.

“A Dazzling, Many-Colored Cataract of Light”

With the stage set, it was time for the showstopper. Asbury Harpending, the enthusiastic promoter, was entrusted with a heavy buckskin sack that the swindlers claimed was from their latest trips to the field. He rushed back to his San Francisco home, where the other investors, including William Ralston, were waiting. Wasting no time on ceremony, Harpending spread a sheet over his billiard table, cut the sack open, and upended it.

He would later describe the contents pouring out in “a dazzling, many-colored catacact of light.” Thousands of glittering stones cascaded across the green felt, a visceral, spectacular sight designed to overwhelm the senses and short-circuit any pesky logical objections. It was a moment of pure, unadulterated financial ecstasy. And it worked perfectly.

Putting a Price on a Lie

Spectacle is one thing, but Gilded Age money needed an expert’s validation. Arnold and Slack happily obliged.

The crucial seal of approval came from Charles Lewis Tiffany. His firm’s erroneous appraisal of a small sample bag at an astronomical $150,000 was the linchpin that secured the venture’s financing. With Tiffany’s name attached, who could doubt it?

To cement their credibility, the syndicate also hired Henry Janin, a highly respected mining engineer, to provide an expert opinion. Janin produced a “wildly enthusiastic” report confirming the field’s authenticity. Of course, his objectivity might have been slightly clouded by the fact that he was paid a hefty fee and given stock options, which he immediately sold for a quick $30,000 profit well before the hoax was exposed. With the world’s most famous jeweler and a top engineer on board, the Great Diamond Hoax was no longer a story. It was reality.

The Unraveling: The Scientist vs. The Swindle

For months, the diamond hoax existed in a world of hype, speculation, and backroom deals. It was a reality built on greed and grandiose promises. But now, it was about to collide with a very different world: the world of hard, empirical fact. And fact, as they say, is a stubborn thing.

The Skeptic on the 40th Parallel

The news of the diamond discovery eventually reached the ears of Clarence King, and he was, to put it mildly, skeptical. King was the opposite of the Gilded Age speculator. He was a brilliant, Yale-educated geologist leading the U.S. Geological Exploration of the Fortieth Parallel—a massive, government-funded project to systematically map the resources of the West.

His suspicion wasn’t just a hunch; it was an offense to his professionalism. The supposed diamond field was located smack in the middle of the territory his team had just spent years surveying with painstaking care. King couldn’t believe they had missed a discovery of this magnitude. Because, as he rightly suspected, they hadn’t. For King, this wasn’t about money. It was about the integrity of his map.

Geology for Detectives

King didn’t run to the newspapers with his doubts. He moved with the methodical precision of a scientist. Through clever deduction and by interviewing railroad men and other locals, he and his team managed to pinpoint the likely location of the salted field. In early November 1872, under the guise of a winter survey, they rode out to the remote mesa.

What took only a few hours to discover made the world’s most powerful financiers look like amateurs. The evidence of fraud was everywhere, obvious to a trained eye:

They found that for every one diamond, there were about twelve rubies - a strangely consistent ratio for a natural deposit.

They noticed that gems were only found in soil that had clearly been disturbed. A quick dig revealed that the untouched earth and solid bedrock below were completely barren.

Most damningly, one of King’s men came upon a diamond that bore the unmistakable marks of a lapidary’s cutting tool. It led to the now-famous (and possibly embellished) exclamation from one of the crew: “This is the bulliest diamond field as never was. It not only produces diamonds, but cuts them moreover also!”

The swindlers had made a critical mistake. They had created a geological impossibility, scattering gems together that didn’t form in the same conditions. To a scientist like King, the field might as well have been a signed confession.

The Bubble Bursts

With ironclad proof in hand, King acted swiftly. On November 10th or 11th, 1872, he sent a telegram to the board of directors of the San Francisco and New York Mining and Commercial Company, officially informing them that they had been the victims of an elaborate fraud.

A couple of weeks later, on November 25th or 26th, the story exploded into public view. The San Francisco Evening Bulletin and San Francisco Chronicle ran massive exposés, laying out King’s findings in humiliating detail. The news spread across the country by telegraph. The Great Diamond Hoax was over. The bubble had burst, leaving the titans of industry looking like fools and turning Clarence King into a national hero overnight.

The Fallout: Ruin, Reputation, & Revenge

The exposure of the hoax wasn’t an ending; it was the beginning of a messy, public cleanup. While Clarence King became a national hero, the swindlers and the swindled had to face the consequences - or, in some cases, artfully dodge them.

The Great Escape & the Tragic Fall

If you’re hoping for justice, you might want to look away. Philip Arnold, the mastermind, got away with it. Mostly. He was tracked to his native Kentucky and sued by the investors. Still, in a final, brilliant move, he negotiated an out-of-court settlement, returning only about $150,000 of his profits. With the rest of his fortune, he purchased a large home and farmland, establishing himself as a local banker. In a fittingly violent end for a Gilded Age hustler, he was shot in a feud with a rival banker years later and died of pneumonia from his wounds in 1878. He died a wealthy and respected, if feared, member of his community.

His cousin, John Slack, the quiet partner, vanished from the main stage. Some accounts say he was never heard from again, disappearing back into the mists of the American West. A more plausible, if less romantic, history tracks him to St. Louis and then to White Oaks, New Mexico, where he reportedly worked as a casket maker and undertaker, living quietly until he died in 1896.

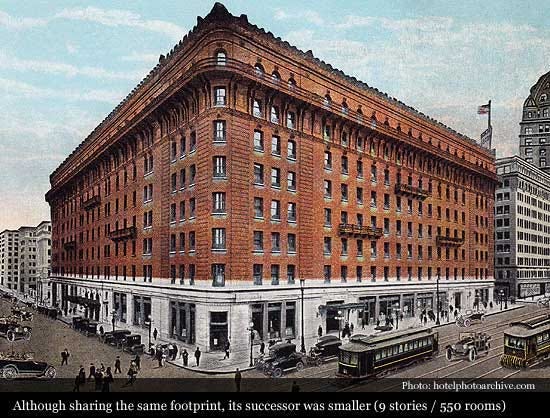

The man they duped most thoroughly, William Ralston, met a far more tragic end. In a desperate bid to save his reputation, he personally reimbursed the initial stockholders for their losses. But the scandal, combined with his other risky ventures, created an atmosphere of financial instability. In August 1875, a run on the Bank of California led to its doors being forced to close. The very next day, Ralston, the man who built San Francisco, was found drowned in San Francisco Bay, a suspected suicide.

The Price of Gullibility

The other players were left to deal with the professional fallout. Asbury Harpending spent the rest of his life and a good chunk of his 1913 memoir desperately trying to convince the world he was an innocent victim, not a co-conspirator. He even won a libel suit against the London Times for accusing him of being the plot’s “mastermind.”

Charles Lewis Tiffany and his company suffered a major embarrassment, but the Tiffany & Co. brand was powerful enough to survive the scandal with little lasting damage. The incident served as a costly lesson in gemology.

Perhaps the most poignant legacy was the one William Ralston left behind in his office. According to Harpending’s account, after Ralston personally reimbursed the investors, he had all of their receipts elegantly framed. He then hung them on the wall of his private office at the Bank of California—a constant, visible reminder of the high price of both gullibility and honor in the world of Gilded Age finance.

More Than a Hoax, A Historical Marker

In the end, the Great Diamond Hoax of 1872 wasn’t just a clever crime. It was a parable for its time. It held up a perfect mirror to the Gilded Age, reflecting both its boundless ambition and its profound gullibility. The story of two Kentucky cousins who sold a lie to the nation’s most powerful men is a cautionary tale about the dangers of greed. Still, it’s also something more: a historical landmark that signals a significant turning point in American culture.

The affair was a battle for what kind of truth America would trust. On one side was the speculative mania of the Gilded Age, a world where grand promises from rich men were enough to launch a $10 million company. On the other hand was the emerging authority of institutional science, represented by the methodical, evidence-based work of Clarence King. The public’s celebration of King’s role was, therefore, a celebration of a new model of authority - one based on verifiable proof rather than on financial power.

The legacy of the hoax is written in the lives it changed. It led to the ruin of William Ralston, cemented the legend of Tiffany & Co.’s fallibility, and, most importantly, it made Clarence King a national hero. His newfound fame directly propelled him to become the first director of the newly formed United States Geological Survey (USGS) in 1879. The hoax, in its spectacular failure, helped solidify the very institution that would prevent such a grand, geology-based fraud from ever happening again. It was a swindle born from the myths of the American West, and its exposure helped cement the triumph of scientific fact.

Resources

Alta California. (1872, November 26). The diamond fields. Volume 24, Number 8274. https://cdnc.ucr.edu/

Britannica. (n.d.). Ralston's Palace Hotel [Photograph]. Britannica. https://cdn.britannica.com/49/129449-050-E618A649/Palace-Hotel-San-Francisco-1875.jpg

Harpending, A. (1913). The great diamond hoax and other stirring incidents in the life of Asbury Harpending. The James H. Barry Co. https://archive.org/details/greatdiamondhoax00harprich/

Library of Congress. (n.d.). The great diamond swindle [Illustration]. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/99404755/

Salt Lake Herald. (1872, November 28). The diamond bubble burst. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85058130/1872-11-28/ed-1/seq-2/

The Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley. (n.d.). William C. Ralston [Photograph]. Online Archive of California. https://oac.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/tf5p3004hn/?brand=oac4

U.S. Geological Survey. (n.d.). Clarence King, USGS Director 1879-1881 [Photograph]. https://www.usgs.gov/media/images/clarence-king-usgs-director-1879-1881

Wood, G. H. (2005). The Great Diamond Hoax. Earth Sciences History, 24(2), 225-227.

Zollinger, J. A. (2017). "The Most Gigantic and Barefaced Swindle of the Age": The Great Diamond Hoax of 1872 and the American Public. [Master's thesis, California State University, Sacramento]. ScholarWorks. https://scholarworks.calstate.edu/downloads/cj82k8579