The Enforcer: How Frank Nitti Built, Ran, and Died for the Chicago Outfit

He was the quiet bookkeeper to Capone’s celebrity gangster. But Frank Nitti was the real power in Chicago, a calculating leader whose reign ended in a lonely, desperate act of self-destruction.

Let’s be honest, when you think of the Chicago mob, you think of one person: Al Capone. He’s the main character, the guy with the scar and the swagger who became a dark American icon. But what happened after the feds shipped him off to Alcatraz for, of all things, tax evasion? The Chicago Outfit - a sprawling, violent, multi-million-dollar corporation - didn’t just close up shop. Someone had to run the store. That someone was Frank Nitti.

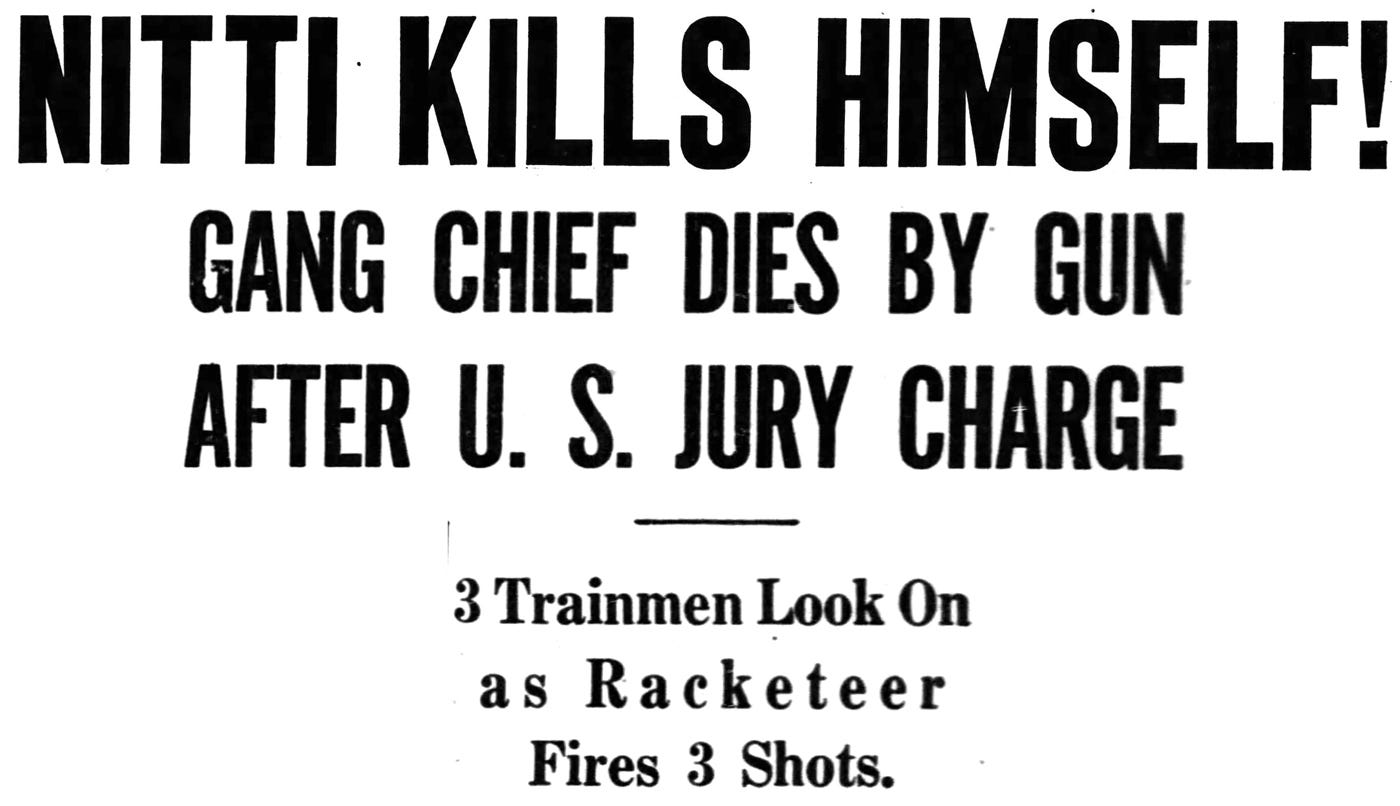

And if you want to understand Frank Nitti, you have to start at the end of his story, because it’s one of the most bizarre and pathetic exits in the history of organized crime. On March 19, 1943, Nitti, acting boss of the Outfit, walked out to a railroad yard, put a .32 revolver to his head, and pulled the trigger. He missed. He fired again. He missed again. The man who ran the most ruthlessly efficient criminal machine in the country couldn’t even manage to kill himself properly. The third shot finally did the job.

This is the central mystery of Frank Nitti. He was known as “The Enforcer,” Capone’s top lieutenant, a man respected for his quiet competence and business acumen. He successfully steered the Outfit through the end of Prohibition, expanding its reach into labor unions and Hollywood with terrifying success. This wasn’t a man who failed. So, how does he end up alone, drunk, and fumbling with a handgun by a railroad track?

The story of Frank Nitti gets overshadowed by the Capone myth, but it’s a far more fascinating look at how power actually worked in the American underworld. It’s a story about the guy in the back room who gets shoved into the spotlight, and what happens when the pressure finally becomes too much to bear. So, let’s dig in. Let’s go past the legend and look at the ledger.

The Man Who Knew How to Listen

Every mob boss has an origin story, and they usually involve a whole lot of ambition and a noticeable lack of other options. Frank Nitti’s is no different, but it has a twist. He wasn’t born a tough guy; he was born a businessman, and his first office was a barbershop.

Born Francesco Raffaele Nitto in 1886, he came over from Italy with his family and landed in Brooklyn. If this sounds familiar, it’s because it was the same neighborhood that produced Al Capone. While the newspapers would later get it wrong and call them cousins, the reality is more practical: they were simply products of the same environment, and Nitti was friends with Capone’s older brothers. While Capone was making a name for himself as a hot-headed bouncer and gangster, Nitti took a quieter route. He became a barber, and in doing so, he became a professional listener.

Think about it: who hears all the neighborhood gossip, all the boasts, all the quiet complaints? The barber. Nitti used his position to become a fence - a guy who buys and sells stolen goods. He learned the art of the deal, how to connect people, and how to stay out of the spotlight. When he eventually left Brooklyn for the booming, lawless world of Chicago around 1913, he brought this skill set with him. He was still cutting hair, but his real money came from jewel theft and, as Prohibition dawned, the incredibly lucrative business of bootlegging.

This is where he gets back on Al Capone’s radar. Capone, now the right-hand to Chicago kingpin Johnny Torrio, wasn’t just looking for trigger-happy thugs. He needed guys who could manage the immensely complex logistics of smuggling Canadian whisky and distributing it across a city of speakeasies. Nitti was perfect. He was organized, discreet, and understood that the real money wasn’t in the violence itself, but in the smooth operation it protected. Capone put him in charge of money and distribution, and Nitti excelled. He earned his famous nickname, “The Enforcer,” not because he was the guy breaking legs, but because he was the guy who made sure the system worked, quietly and effectively. He ensured the Outfit’s will was enforced.

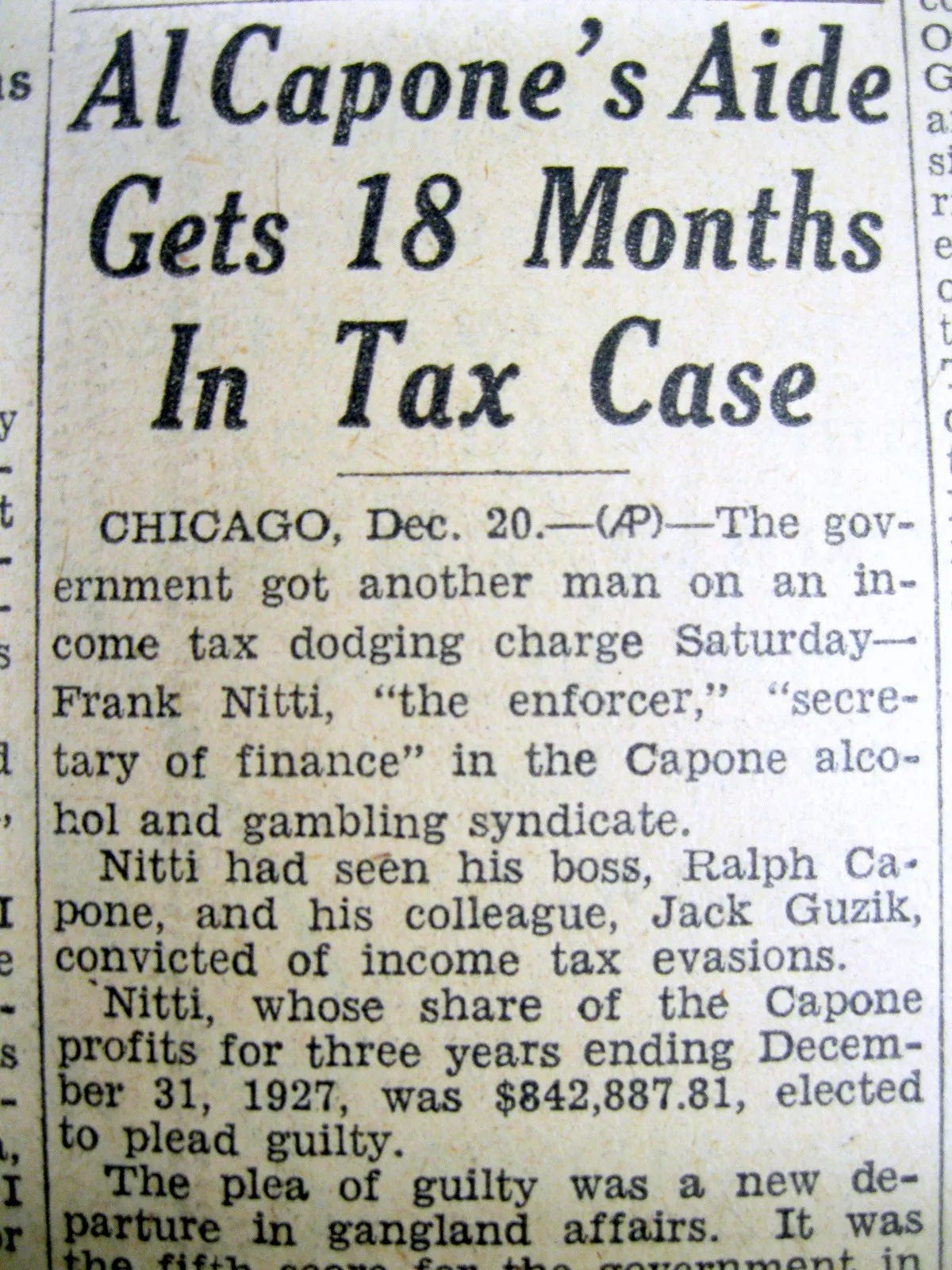

Of course, even the quiet guys get caught. As the feds closed in on the entire Capone organization, they hit Nitti with the same charge that would bring down his boss: income tax evasion. In 1930, he was sentenced to 18 months in the federal penitentiary at Leavenworth. For a man accustomed to running his own life, being locked in a tiny cell was a special kind of hell. It wasn’t just the loss of freedom; it was the physical confinement. The experience scarred him, leaving him with a severe, lifelong claustrophobia. When he walked out of prison, he was heading for the top job in the American underworld, but he was carrying a deep-seated psychological wound that would, years later, play a central role in his undoing.

The Boss in the Crosshairs

When Frank Nitti became the acting boss of the Chicago Outfit in 1932, it wasn’t exactly a coronation. It was more like being named captain of a sinking ship that was also on fire. Prohibition, the cash cow that had financed the entire operation, was on its last legs. The Outfit’s ranks were full of ambitious, violent men, like the notoriously vicious Paul “The Waiter” Ricca, who saw Nitti as more of a placeholder than a true king. To top it off, the new mayor of Chicago, Anton Cermak, decided to make his mark by taking out the new head of the mob.

On December 19, 1932, this wasn’t just a political threat; it became brutally real. A team of Chicago police detectives, acting as Cermak’s personal hit squad, stormed Nitti’s downtown office at 221 North LaSalle Street. They opened fire, shooting the new boss three times in the back and neck. To make it look “legit,” the lead detective, Harry Lang, then shot himself in the arm to fabricate a self-defense claim. It was an audacious, gangland-style hit carried out with police badges. There was just one problem: Nitti lived.

What happened next was pure, uncut Chicago absurdity. Not only did Nitti survive, but the case against him for “assaulting” the police officers fell apart in court in the most spectacular fashion. One of the cops involved testified that Nitti was unarmed. Another admitted that Detective Lang had been paid a $15,000 bounty for the murder. Nitti was acquitted, and his failed hit backfired beautifully. It made him a legend. He’d faced down the mayor and a crooked police force and walked away, transforming him from a stand-in to the undisputed boss in the public eye.

With his position solidified, Nitti did what he did best: he got down to business. He proved to be a visionary leader, engineering a massive pivot for the Outfit. Recognizing the Prohibition was a dead end, he shifted the organization’s focus to more durable rackets. He pushed his Outfit deep into labor racketeering, seizing control of unions to extort legitimate businesses. He expanded their gambling empires. And most significantly, he set his sights on the glittering prize of Hollywood, laying the groundwork for a shakedown that would funnel millions from the studio system back to Chicago.

This was Nitti’s real talent. Capone was a celebrity, a bootlegger who became a national figure. Nitti was a CEO. He was quiet, he delegated the dirty work, and he was interested in profit and power, not headlines. Under his leadership, the Outfit became more mature, diversified, and arguably more dangerous corporation. He had survived the end of Prohibition and a police-led assassination attempt. By all accounts, he should have been set for a long and prosperous reign. But the very scheme that was his crowning achievement - the extortion of Hollywood - was already planting the seeds of his destruction.

The Hollywood Shakedown

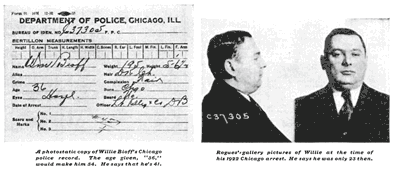

Having solidified his power in Chicago, Frank Nitti turned his attention west. The target: Hollywood. The movie industry was awash in cash and, Nitti figured, ripe for the picking. The plan he put into motion was a masterclass in extortion, relying not on brute force but on a single, critical choke point. The key to the whole operation was two men: George Browne, the corrupt president of the stagehands’ union (IATSE), and a former pimp and street-level thug named Willie Bioff.

The setup was almost laughably simple. With Browne in their pocket, the Outfit controlled the union for every movie projectionist in the country. This gave them an industrial-scale kill switch. If a studio - MGM, Paramount, 20th Century Fox, any of them - didn’t want to play ball, the Outfit could call a strike and shut down every single one of their theaters. No movies, no money. The studio heads, terrified of the financial catastrophe a nationwide strike would cause, had no choice. They paid.

And they paid millions. Willie Bioff, acting as the Outfit’s man on the ground, would collect huge cash “gifts” from the studios to ensure “labor peace.” The money flowed from sunny California back to the gray streets of Chicago, and for a few years, it was the perfect crime. The problem, as is so often the case, was human stupidity. Willie Bioff couldn’t resist the Hollywood lifestyle he was extorting. He bought a huge ranch, wore expensive suits, and generally acted like a big shot, which is a terrible idea when your official job is “union organizer.” The press and the IRS started sniffing around, wondering how this guy was living like a studio mogul on a union salary.

Predictably, the whole thing came crashing down. Bioff was indicted for tax evasion, and he quickly turned federal informant to save his own neck. He laid out the entire scheme for the government, and in 1943, the hammer fell. A federal grand jury in New York indicted the entire senior leadership of the Chicago Outfit for their role in the conspiracy. The names on the list included the Outfit’s ambassador to Hollywood, Johnny Roselli, the rising power Paul “The Waiter” Ricca, and the big boss himself, Frank Nitti.

This was a disaster. The indictments were federal, meaning a one-way ticket to a serious penitentiary, far from the friendly confines of the Illinois justice system. The Outfit’s board of directors held a crisis meeting, and a cold, hard decision was made. Someone had to take the fall to protect the organization. Paul Ricca, the man who was quickly becoming the real authority, argued that it had to be Nitti. He was the boss, it was his name on the letterhead, and - this is where it gets truly cruel - everyone knew about Frank’s intense claustrophobia. They knew he was terrified of being locked in a cell again. They weren’t just asking him to go to prison; they were leveraging his deepest psychological fear to convince him. He was backed into a corner, not just by the law, but by his own men. The Enforcer was being strong-armed.

A Lonely End on the Tracks

March 19, 1943, was the day Frank Nitti had to give his answer. The day before his scheduled grand jury appearance, he had breakfast with his wife, Anna. When she left to go to church, he told her he was just going for a walk. Instead, he went to the liquor cabinet and began to drink heavily. The man who had faced down police assassins was now facing a threat he couldn’t beat: a 6-by-9-foot prison cell. His deepest fear was about to become his reality, and his own organization had just handed him the train ticket.

Sometime that afternoon, Nitti stuffed a .32 caliber revolver into his coat pocket and stumbled out of his comfortable home in Riverside. He walked five blocks to a sprawling, dirty Illinois Central railyard. As a freight train crew was slowly backing their caboose down the line, they saw him—a well-dressed man, staggering along the tracks as if he were drunk, which, of course, he was. The crewmen yelled at him to get out of the way. Nitti obliged, stepping off the tracks and over to a nearby fence. Then, as the caboose drew even with him, he put the gun to his head.

What happened next, as reported by the shocked train crew, was a moment of pure, tragic farce. The first shot ripped through his hat. A clean miss. He tried again. The second bullet also missed his skull. Finally, as the train workers ducked for cover, believing they were being shot at, Nitti managed to press the muzzle behind his right ear and fire a third fatal shot. The Enforcer was dead.

When the police arrived, they found the notorious gang leader slumped against the fence. An autopsy later revealed his blood alcohol level was 0.23 - nearly three times the modern legal limit to drive. The official coroner’s jury ruled it a suicide, committed “while temporarily insane and in a despondent frame of mind,” which has to be the most clinical understatement in the history of mob deaths.

Nitti’s legacy is a complicated one. He is so often dismissed as Capone’s puppet or a glorified bookkeeper. But that’s selling him short. Nitti was the man who successfully navigated the Outfit through its most perilous transition, pivoting from the dying racket of bootlegging into the more stable and lucrative enterprises of gambling and union extortion. He was a brilliant, if ruthless, CEO. But he was never a king. He lacked Capone’s charisma and stomach for the spotlight. He was a manager, not a celebrity, and when the Hollywood scheme forced him onto the national stage, he was fatally exposed. His death marked the end of an era, but also a transfer of power to the even more calculating and discreet Paul Ricca, who would steer the Outfit for decades. Nitti built the modern Chicago mob, and in the end, it devoured him.

The Ledger is Closed

In the end, Frank Nitti wasn’t brought down by a rival gangster or a G-man’s bullet. He was crushed by the weight of the very empire he helped build. He was a man of profound contradictions: a quiet family man who ran a violent criminal syndicate; a brilliant strategist undone by a personal phobia; a powerful boss who died helpless and alone. His story is a stark reminder that in the world of organized crime, the house always wins. The power, the money, the fear - it’s all a loan. And eventually, the ledger has to be balanced. For Frank Nitti, the final payment was made with three pulls of a trigger in a cold, lonely railyard.

References

A&E. (2021, February 21). Mobsters: Frank Nitti - Full Episode (S2, E5) [Video]. YouTube.

Binder, J. J. (2003). The Chicago Outfit. Arcadia Publishing.

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. (n.d.-a). Frank Nitti. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved July 21, 2025, from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Frank-Nitti

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. (n.d.-b). Paul Ricca. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved July 21, 2025, from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Paul-Ricca

Chicago Outfit. (n.d.). Wikipedia. Retrieved July 21, 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chicago_Outfit

Eghigian, M. (2006). After Capone: The life and world of Chicago mob boss Frank "The Enforcer" Nitti. Cumberland House.

Federal Bureau of Investigation. (n.d.). FBI Records: The Vault — Frank Nitti. U.S. Department of Justice. Retrieved July 21, 2025, from https://vault.fbi.gov/frank-nitti

Film Noir Foundation. (n.d.). How the Mob and the movie studios sold out the Hollywood labor... Retrieved July 21, 2025, from http://www.filmnoirfoundation.org/noircitymag/The-Chicago-Way.pdf

Frank Nitti. (n.d.). Wikipedia. Retrieved July 21, 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frank_Nitti

Gershon, L. (2024, November 17). How Al Capone made greyhound racing great. JSTOR Daily. Retrieved from https://daily.jstor.org/how-al-capone-made-greyhound-racing-great/

Harry Caray's Restaurant Group. (n.d.-a). Nitti. Retrieved July 21, 2025, from https://www.harrycarays.com/nitti.html

Harry Caray's Restaurant Group. (n.d.-b). Nitti's Speakeasy. Retrieved July 21, 2025, from https://www.harrycarays.com/nittisspeakeasy.html

Historic and Vintage Newspapers. (n.d.). 1930 newspaper AL CAPONE enforcer FRANK NITTI is sentenced to prison TAX EVASION [Online listing]. eBay. Retrieved July 21, 2025, from https://www.ebay.com/itm/275859642496

Humble, R. D. (2007). Frank Nitti: The true story of Chicago's notorious "enforcer". Barricade Books.

Joseph, J., & Smith, C. M. (2021). The ties that bribe: Corruption's embeddedness in Chicago organized crime. Criminology, 59(4), 705–731. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9125.12281

Library of Congress. (1932). [Frank Nitti, three-quarter length portrait, facing right]. Prints and Photographs Division. Retrieved July 21, 2025, from https://www.loc.gov/item/95511445/

Lindberg, R. C. (2016). Gangland Chicago: Criminality and lawlessness in the windy city. Rowman & Littlefield.

My Al Capone Museum. (n.d.). Frank Nitto. Retrieved July 21, 2025, from https://www.myalcaponemuseum.com/id41.htm

The Mob Museum. (n.d.-a). Paul “The Waiter” Ricca. The National Museum of Organized Crime and Law Enforcement. Retrieved July 21, 2025, from https://themobmuseum.org/notable_names/paul-ricca/

The Mob Museum. (n.d.-b). Tony Accardo. The National Museum of Organized Crime and Law Enforcement. Retrieved July 21, 2025, from https://themobmuseum.org/notable_names/tony-accardo/

United States of America, Plaintiff-appellee, v. Frank Nitti, Defendant-appellant, 444 F.2d 1056 (7th Cir. 1971).

Valle, G. (2024, April 6). The story of Frank Nitti, Al Capone's right-hand man who took over the Chicago Outfit. All That's Interesting. Retrieved July 21, 2025, from https://allthatsinteresting.com/frank-nitti

Weigman, C. (1943, March 20). Frank Nitti kills self! Chicago's no. 1 gangster. Chicago Daily Tribune. Sourced via Chicagology.com.