The Ice Cream Blonde's Cold Case: Who Really Killed Thelma Todd?

In 1935, a movie star was found dead in her garage. The cops called it an accident. The evidence screamed murder. Let's dig into the cover-up.

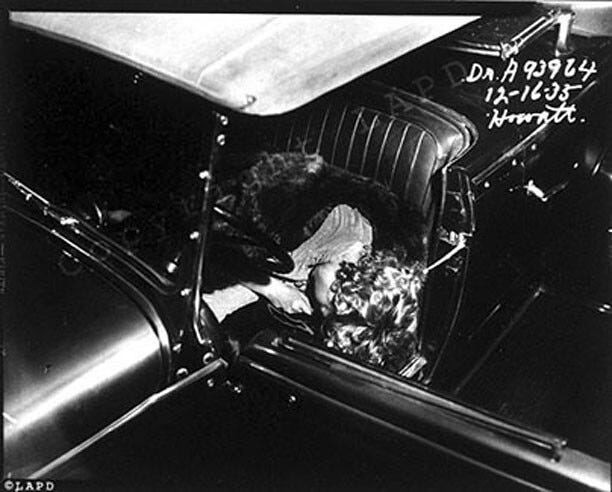

When Thelma Todd’s maid found her on the morning of December 16, 1935, it was clear something was terribly wrong. The famous 29-year-old actress was dead in the front seat of her convertible, parked in the garage of her business partner and lover, Ronald West. The cause of death was obvious enough - carbon monoxide poisoning.

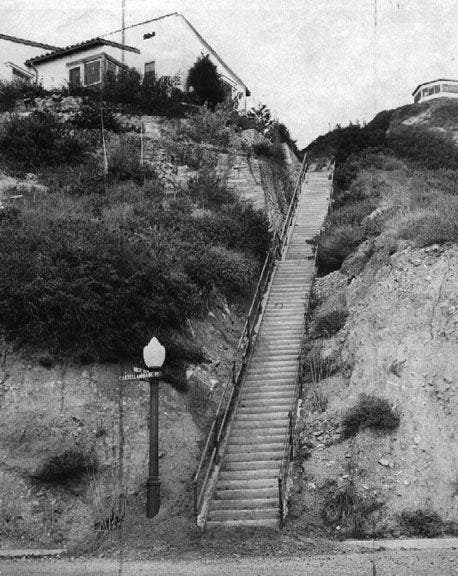

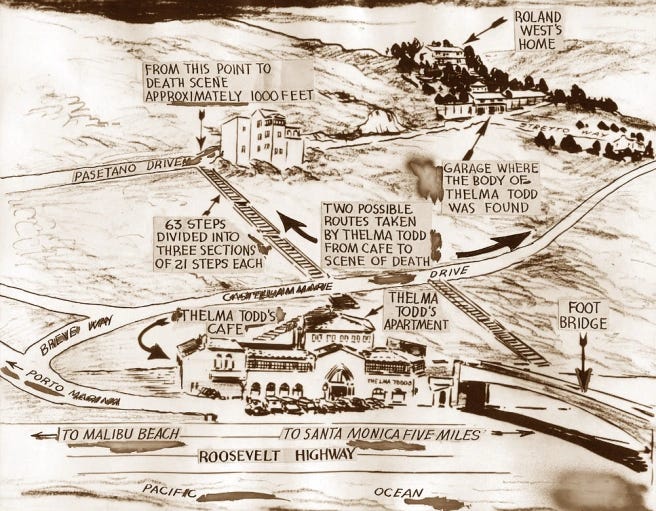

The Los Angeles authorities stitched together a story with remarkable speed. They claimed Todd, finding herself locked out of her apartment after a party, made the long, dark climb up 271 steps to the garage. To stay warm, she supposedly turned on her car’s engine and was tragically overcome by the exhaust fumes. The grand jury called it an “accidental death,” closing the case with a neat, tidy bow.

It was a good story. The only problem was the evidence.

The facts pointed to a scene that was anything but simple. They raised questions that the investigators seemed strangely determined to ignore. For instance, how did a woman in delicate evening shoes and silk stockings climb a steep, unpaved hillside without getting a single speck of dirt on them? Why did witnesses report seeing her alive and well a full day after she had supposedly died in the garage? And what about the reports of a broken nose and cracked ribs on a body that the official autopsy claimed had “no marks of violence?”

The official investigation into Thelma Todd’s death wasn’t just flawed; it was a masterclass in avoiding the obvious. So, let’s do what they didn’t. Let’s look at the evidence, the suspects, and the powerful forces at play in a town built on illusion.

More Than a Punchline: The World of Thelma Todd

To understand why Thelma Todd’s death was so convenient for so many people, you first have to understand that the woman she played on screen - the effervescent, wisecracking “Ice Cream Blonde” - was mostly an act. Yes, she was a gifted comedienne who held her own against the Marx Brothers and Laurel & Hardy, but off-screen, Thelma Todd was playing a much more serious game. She was a sharp, ambitious businesswoman who saw the writing on the wall: in Hollywood, a beautiful actress had a shelf life.

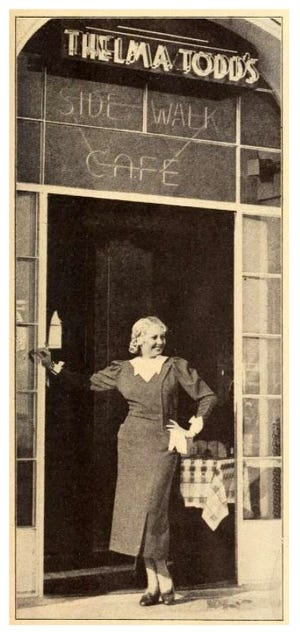

Recognizing the fleeting nature of stardom, she sought financial independence from the studio system that could discard her at a moment’s notice. Her solution was Thelma Todd’s Sidewalk Café, a picturesque restaurant located right on the Pacific Coast Highway. Opened in 1934, this wasn’t some vanity project; it was a serious enterprise and a roaring success, quickly becoming a popular spot for both tourists and Hollywood’s elite. Todd was the consummate host, greeting patrons and building a brand that was all her own. This was a pragmatic, forward-thinking woman, a characterization that stands in stark contrast to the helpless or desperate person the police later described.

Her bid for independence, however, put her directly in the crosshairs of powerful and dangerous men. Her business partner and lover, the director Roland West, was known to be a jealous and controlling man with a volatile temper. Their relationship was reportedly filled with conflict over the café’s finances and West’s resentment of her social life. Then there was her ex-husband, Pat DiCicco, a film agent with known mob connections and a history of physical abuse. Their public, bitter argument at a party just hours before she disappeared was common knowledge. Todd had already cut him out of her life and her will, leaving him a deliberately insulting sum of just $1 to ensure he couldn’t contest it.

Looming over all of this was the specter of organized crime. The mob saw Hollywood’s wealth as fertile ground, particularly for illegal gambling operations. An exclusive club like the one on the second floor of Todd’s café was precisely the type of establishment they coveted. This brought Todd into a world far more dangerous than studio politics, forcing her to fend off pressure to use mob-controlled suppliers and resist attempts to install high-stakes gambling rooms.

It all created the perfect storm. Thelma Todd was a star trying to build a life outside the rigid control of the studio system and its moralistic Hays Code, which demanded a scandal-free image at all costs. Her café, intended as a safe harbor, had instead become a locus of conflict, placing her at the dangerous intersection of a controlling lover, a violent ex-husband, and the predatory criminal underworld.

The Final 48 Hours

To understand how thoroughly the investigation was bungled, you have to have a clear picture of Thelma Todd’s last known movements. The official police theory accounts for only a few hours, while credible witnesses suggest a timeline that is much longer and far more mysterious.

Saturday Night

The weekend begins at a star-studded party at the Trocadero nightclub on the Sunset Strip, hosted by actress Ida Lupino. Thelma is there, mingling and enjoying herself, but the night is soured by a public and reportedly “unpleasant” argument with her hot-headed ex-husband, Pat DiCicco. This encounter establishes a clear point of conflict with a man known for his violent temper, just hours before she would disappear.

Early Sunday Morning

Around 3:45 AM, Todd’s chauffeur, Ernest Peters, drives her home to her apartment above the Sidewalk Café. When they arrive, she declines his offer to walk her to her door, and he watches her head toward the entrance. This is the last time Thelma Todd is seen alive by an undisputed witness. According to the police, she found herself locked out, walked up the hill to the garage, started the car, and died shortly thereafter.

But that’s not what the evidence says.

The Phantom Sunday

The official police timeline effectively ends before sunrise on Sunday, but multiple witnesses place Todd alive and active throughout the day.

The first clue that something was amiss came from the autopsy itself, which found undigested food (including peas) in her stomach. Peas were not on the menu at the Trocadero, meaning she had to have eaten a meal sometime on Sunday, long after she was supposedly dead.

The timeline is then completely fractured by two key witness statements. First, Jewel Carmen - the estranged wife of Roland West - testified to the grand jury that she saw Thelma Todd on Sunday afternoon, driving in her car with a “strange man.” Later, Todd’s friend, as Mrs. Wallace Ford, told police she received a phone call around 4:30 PM from a woman she was certain was Todd, asking if she could bring a male guest to a party that evening. These accounts, if true, prove the “locked out” narrative is false and introduce a mystery companion into her first hours.

Monday Morning

At approximately 10:30 AM, after not hearing from her employer, Mae Whitehead, Todd’s maid, goes looking for her. She walks up to the garage and discovers Thelma’s body inside her car. The mystery of the “Phantom Sunday” was not a homicide case - or at least, it should have been.

A Compendium of Contradictions: The “Investigation”

When investigators arrived at the Castillo de Mar garage on December 16th, the scene seemed, at first glance, straightforward. But the moment they looked closer, the simple story of an accidental death began to fall apart, replaced by a cascade of baffling and contradictory evidence. It’s in these details that the official narrative falls apart, and a homicide investigation should have been initiated.

The Scene of the “Accident”

Thelma Todd was found slumped in the driver’s seat of her 1934 Lincoln Phaeton. Her expensive diamond jewelry remained untouched, and her mink wrap was still in place, effectively ruling out robbery as a motive. The car’s ignition key was in the “on” position, but the engine was silent and the battery was completely dead. The first head-scratcher, however, was the fuel tank, which still contained about 2.5 gallons of gasoline. This directly contradicted the theory that she had run the engine for warmth until the tank was empty.

The Case of the Spotless Shoes

The biggest red flag was Todd’s clothing. She was wearing the delicate mauve and silver gown she had worn to a party at the Trocadero. More importantly, her silk stockings and evening shoes were in pristine condition, showing no scuffs, tears, or dirt.

This is fundamentally inconsistent with the police theory that she walked up the 271 steep, unpaved, and likely muddy outdoor steps from the café to the garage on a cold night. In a moment of brilliant, practical police work, a female officer later recreated the climb for the investigation; she found her own shoes were noticeably scuffed from the effort. The immaculate state of Todd’s attire strongly suggests one simple truth: she never made that walk.

An Autopsy from Two Planets

The official cause of death was acute carbon monoxide poisoning. Beyond that, the official report painted a picture of a body almost entirely free of trauma. The autopsy surgeon, Dr. A.P. Wagner, testified at the coroner’s inquest that he found only a “superficial contusion on the lower lip.” He insisted there were “no marks of violence anywhere upon or within the body.”

This sanitized account stands in direct opposition to a wealth of reports from journalists and other investigators. These accounts describe a body bearing the marks of a violent assault, including a broken nose, a chipped tooth, and two cracked ribs.

Furthermore, the toxicology report introduced a critical inconsistency that supports the “Phantom Sunday” timeline we’ve established. The autopsy revealed undigested food, including peas, in Todd’s stomach, which confirms she ate a meal long after leaving the Trocadero party and lends credence to the witness accounts of her being alive on Sunday.

The Timeline Problem: Saturday’s Dress on a Sunday Victim

The timeline of the “Phantom Sunday” creates the single most damning contradiction in the entire case. On the one hand, we have the witness testimony that Thelma Todd was alive and active all day Sunday. On the other hand, we have her body, discovered Monday morning, dressed in the exact same pristine party dress she wore on Saturday night.

This forensic impossibility required investigators to believe one of two scenarios: either multiple, credible witnesses were all mistaken, or Todd, for some inexplicable reason, changed back into her dirty party clothes after a full day of activity right before her death. The authorities chose the former, dismissing the testimony without conducting a thorough investigation. A far more likely scenario, however, is that the crime scene was staged, with her body deliberately dressed in those specific clothes to support the false “locked out right after the party” narrative.

The Lineup: Shady Characters and Convenient Red Herrings

With accident and suicide being highly improbable, homicide emerges as the most logical explanation. The investigation, both at the time and in the decades since, has centered on three primary suspects.

Suspect #1:Roland West, The Controlling Director

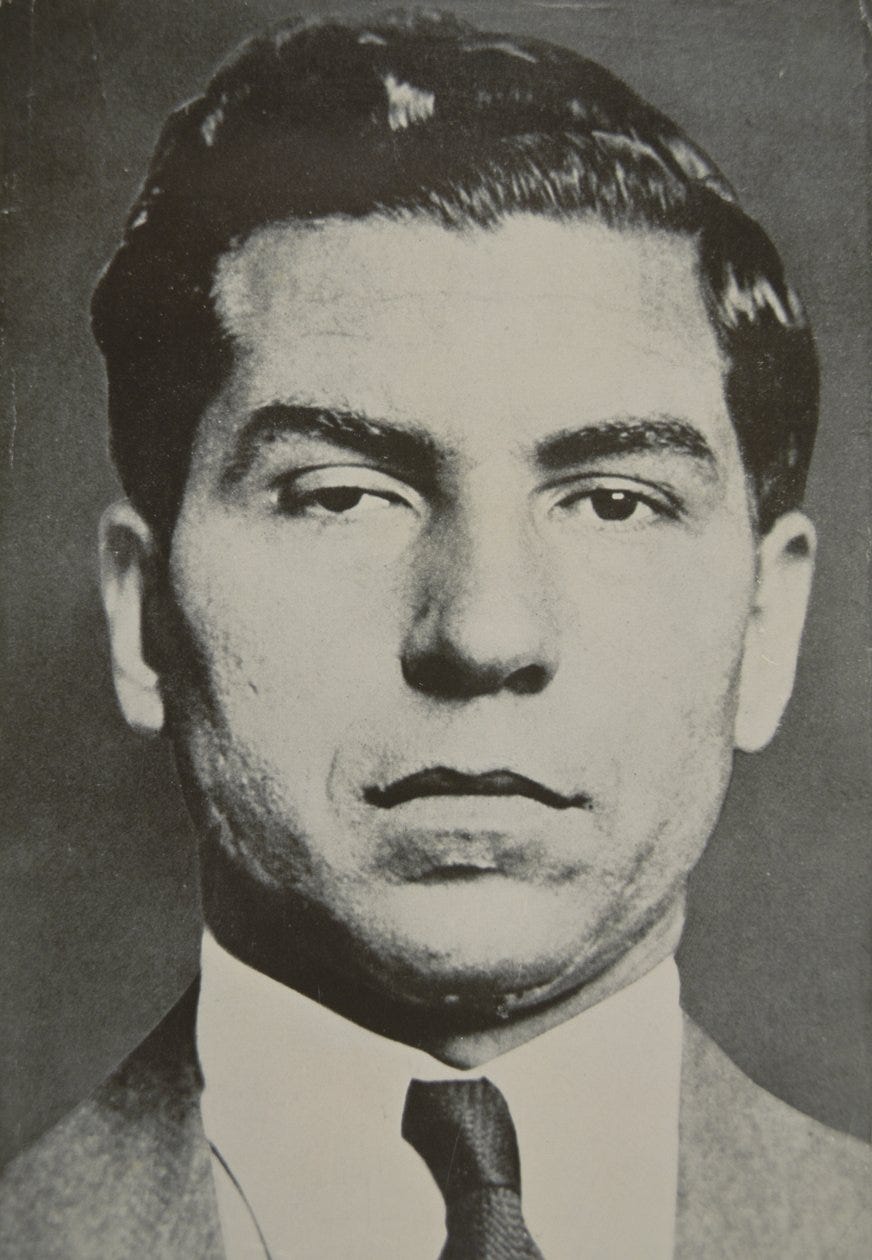

Roland West, Todd’s lover and business partner, is the most prominent and logical suspect.

Motive: West was known to be a jealous, possessive, and controlling man with a “volcanic temper.” Their relationship was reportedly fraught with conflict, especially over the café’s finances and West’s fury at Todd’s active social life. He was a man who wanted control, and Todd was a woman seeking independence.

Opportunity: He had absolute opportunity. He was in his apartment on the property, directly below the one Todd was locked out of, on the night she died. His own contradictory testimony places him at the scene during the crucial hours.

Evidence: West’s testimony before the grand jury was a masterclass in evasion, riddled with contradictions about what he heard and did that night. The most damning evidence, however, is the rumored deathbed confession he allegedly made years later to his friend, actor Chester Morris. In it, West claimed he had argued with Todd and locked her in the garage to “teach her a lesson,” leading to her unintentional death. Furthermore, the likelihood that the death scene was staged - specifically with Todd being dressed back in her party clothes - points to a panicked, personal cover-up. This scenario fits West far better than any other suspect.

Suspect #2: Pat DiCicco, The Hot-Headed Ex

Todd’s ex-husband, Pasquale “Pat” DiCicco, was a film agent with a nasty reputation, known mob connections, and a history of physically abusing her.

Motive: As established in the timeline, his public argument with Todd at the Trocadero party positioned him as a person with a clear, immediate motive for revenge.

Opportunity: While he was at the party with her, there is no direct evidence placing him in the Pacific Palisades later that night.

Evidence: The case against DiCicco is largely circumstantial. It hinges entirely on his violent personality and his role as a link between Todd and the criminal underworld. Without more, he remains a person of interest but a far less likely perpetrator than West.

Suspect #3: Lucky Luciano, The Mob Boss

The most sensational theory involves mob boss Charles “Lucky” Luciano. This narrative posits that Todd was murdered on his orders because she refused to allow illegal, high-stakes gambling in the private club above her restaurant.

Motive: A straightforward business dispute. Todd’s refusal would have been a direct challenge to the mob’s expansion plans in Hollywood.

Opportunity: This is the theory’s glaring weak spot. Luciano’s presence in Los Angeles in December 1935 is unproven and hotly disputed. At the time, he was the prime target of a major prosecution by Special Prosecutor Thomas E. Dewey in New York, making a cross-country trip to handle a restaurant dispute personally seemed highly unlikely.

Evidence: This theory derives its strength from circumstantial details, such as the undigested peas, but it relies heavily on rumor. Moreover, the deeply personal and strange act of re-dressing the body in specific clothes feels inconsistent with a professional mob hit, which is typically more straightforward. This detail makes the crime feel less like a business transaction and more like a desperate, amateur attempt at a cover-up. This theory may have served as a convenient red herring for both the real killer and the authorities.

The Official Story: A Masterclass in Not Looking Too Hard

Given the mountain of contradictory evidence, you would expect the official investigation to have been a tense, forensic battle to uncover the truth. Instead, what transpired was an exercise in futility—a legal process that seemed designed not to solve a crime, but to make it disappear.

The initial coroner’s inquest on December 18, 1935, concluded that the death “appeared accidental,” but with a telling recommendation for “further investigation to be made into the case, by proper authorities.” Even this first jury wasn’t entirely buying the simple story they were being sold. This kicked the case to a Los Angeles County Grand Jury, which convened to investigate the possibility of murder.

For weeks, key figures in Todd’s life, from her close friend ZaSu Pitts to her maid Mae Whitehead, were called to testify. The star witness, however, was Roland West. His testimony was evasive and riddled with contradictions, and he gave conflicting accounts of what he heard and did on the night Thelma Todd died. He was a prime suspect, a man with a clear motive and opportunity, who was demonstrably lying to authorities.

And yet, despite West’s suspicious testimony and the heap of evidence that contradicted the accident theory - the spotless shoes, the conflicting autopsy reports, and the glaring forensic impossibility of the “Phantom Sunday” timeline given the state of Todd’s clothes - the grand jury probe concluded after four weeks with no indictment. The Homicide Bureau officially closed the case, declaring the death “accidental with possible suicide tendencies.” This baffling verdict, which even some jurors reportedly disagree with, was a profound failure on the part of the District Attorney’s office to pursue the obvious signs of homicide.

This inaction aligns perfectly with the “scandal containment” imperative of 1930s Hollywood. The powerful studio system, governed by the strict moral framework of the Hays Code, was terrified of scandal. A murder investigation involving a major star, a director, mobsters, and illicit affairs was a nightmare scenario. The LAPD and the D.A.’s office, notoriously susceptible to Hollywood influence, had immense pressure to classify the death in the least damaging way possible. A quiet “accident” was vastly preferable to a sensational homicide trial that would tarnish the industry’s carefully polished image. The later “destruction” of the official FBI file on the case only strengthens the suspicion that inconvenient truths were deliberately buried.

The grand jury’s failure wasn’t a failure of the jurors; it was an institutional failure of a justice system that, when faced with a powerful and influential industry, chose the path of least resistance.

The Truth in the Hollywood Haze

The official rulings of “accident” and “suicide” in the death of Thelma Todd aren’t just flawed; they’re fundamentally untenable. They require you to ignore a mountain of contradictory evidence, to believe in a timeline full of ghosts, and to accept a story that insults common sense.

When analyzed critically, the facts point overwhelmingly to a homicide. While we can never be certain, the evidence suggests that director Roland West is the most probable perpetrator. His motives of jealousy and control, his clear opportunity, his demonstrably false testimony, and the rumored deathbed confession form a cohesive case that far outweighs the speculative evidence against other suspects. The narrative that West, in a fit of rage, caused Todd’s death and then clumsily staged the scene to look like an accident remains the single most effective theory for reconciling the disparate facts of the case.

The official story asks us to believe in a woman who was active all day Sunday but was found in her pristine Saturday night party dress. A far more plausible story is one of a crime scene deliberately staged, a truth buried under a mink wrap, and a culture of silence. The mystery of Thelma Todd’s death endures not because it was a “perfect crime,” but because it was the product of a profound and systemic failure of justice - a failure fostered by an era when the power of Hollywood to suppress scandal was absolute, and where the truth was too inconvenient to pursue.

References

Associated Press. (1936, January 11). Thelma Todd’s Death Held ‘Accidental’. Healdsburg Tribune. Retrieved from California Digital Newspaper Collection.

The Bizarre Death of Thelma Todd. (n.d.). Frankly, My Dear. Retrieved August 9, 2025, from http://www.franklymydear.com/todd.html

Chiasson, T. (n.d.). Gone Too Soon Blogathon: Thelma Todd (1906-1935) Part Two of Two. My Love of Old Hollywood. Retrieved August 9, 2025, from http://myloveofoldhollywood.blogspot.com/2012/03/gone-too-soon-blogathon-thelma-todd-11.html

Creepy, D. (n.d.). Aggie and the Ice Cream Blonde. Deranged LA Crimes. Retrieved August 9, 2025, from

https://derangedlacrimes.com/?p=13356

Donati, W. (2012). The Life and Death of Thelma Todd. McFarland & Company.

The Era of Gangster Films. (n.d.). PBS. Retrieved August 9, 2025, from https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/dillinger-era-gangster-films/

Federal Bureau of Investigation. (n.d.). FBI HQ File 62-7209 Thelma Todd. Paper Treason. Retrieved August 9, 2025, from https://papertreason.com/2012/07/20/fbi-hq-file-62-7209-thelma-todd/

Film Star Thelma Todd's Death Cannot Be Explained. (n.d.). EBSCO Research Starters. Retrieved August 9, 2025, from https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/film/film-star-thelma-todds-death-cannot-be-explained

Forgotten Hollywood: The Unsolved Mystery of the Death of Thelma Todd. (2022, June 29). Golden Globes. Retrieved August 9, 2025, from https://goldenglobes.com/articles/forgotten-hollywood-unsolved-mystery-death-thelma-todd/

Hall, S. (n.d.). The tragic end of LA's first celebrity restaurants. KCRW. Retrieved August 9, 2025, from https://www.kcrw.com/culture/shows/good-food/hollywood-celebrity-restaurants-thelma-todd-sidewalk-cafe-preston-sturges-players-club

History.com Editors. (2023, April 4). Charles "Lucky" Luciano. HISTORY. Retrieved August 9, 2025, from https://www.history.com/topics/crime/lucky-luciano

The Ice Cream Blonde: The Whirlwind Life and Mysterious Death of Screwball Comedienne Thelma Todd. (2016, February 16). Hometowns to Hollywood. Retrieved August 9, 2025, from https://hometownstohollywood.com/book-reviews/biographies/the-ice-cream-blonde-the-whirlwind-life-and-mysterious-death-of-screwball-comedienne-thelma-todd/

Lawrence History Center. (n.d.). Thelma Todd Research Files Compiled by Benjamin "Benny" Drinnon (2023.031). Retrieved August 9, 2025, from https://lawrencehistory.org/node/35101

Los Angeles Public Library. (c. 1935). Grand jury probe of Thelma Todd's death [Photograph]. Tessa2.lapl.org. https://tessa2.lapl.org/digital/collection/photos/id/8578/

Maltin, L. (2015, December 18). THELMA TODD IN THE NEWS AGAIN AFTER 80 YEARS. Leonard Maltin's Movie Crazy. Retrieved August 9, 2025, from https://leonardmaltin.com/thelma-todd-in-the-news-again-after-80-years/

Morgan, M. (2015). The Ice Cream Blonde: The Whirlwind Life and Mysterious Death of Screwball Comedienne Thelma Todd. Chicago Review Press.

Morgan, M. (2016, January 10). Interview with Thelma Todd biographer Michelle Morgan. Out of the Past Blog. Retrieved August 9, 2025, from https://www.outofthepastblog.com/2016/01/interview-thelma-todd-biographer.html

The Mysterious Death of Massachusetts Movie Star Thelma Todd. (n.d.). New England Historical Society. Retrieved August 9, 2025, from https://newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/the-mysterious-death-of-massachusetts-movie-star-thelma-todd/

Schreiber, B. (n.d.). Death in Paradise: Thelma Todd. Bradschreiber.com. Retrieved August 9, 2025, from https://www.bradschreiber.com/selected-writing/death-in-paradise-thelma-todd

Staggs, M. (2017, March 23). '30s star Thelma Todd 'was becoming' tired 'of Hollywood' before her mysterious death, book claims. Fox News. https://www.foxnews.com/entertainment/30s-star-thelma-todd-was-becoming-tired-of-hollywood-before-her-mysterious-death-book-claims

Thelma Todd found dead. (1935, December 16). [Photograph]. Calisphere. https://calisphere.org/item/5b1fc68b000041a1ea64f98b20bbbe29/

Thelma Todd. (n.d.). Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 9, 2025, from https://projects.latimes.com/hollywood/star-walk/thelma-todd/

Thelma Todd's Death Probed. (1935, December 17). Los Angeles Times. Retrieved from https://www.latimes.com/local/obituaries/archives/la-me-thelma-todd-19351217-story.html

Thelma Todd's Tragedy: The Forgotten Life of the Original Celebrity Restaurateur. (2020, December 16). PBS SoCal. Retrieved August 9, 2025, from https://www.pbssocal.org/food-discovery/food/thelma-todds-tragedy-the-forgotten-life-of-the-original-celebrity-restaurateur

United Press. (1935, December 19). Actress Death Still Probed. The San Bernardino Sun. Retrieved from California Digital Newspaper Collection.

Wikipedia contributors. (2025, August 5). Thelma Todd. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thelma_Todd

Wolf, M. J. (n.d.). Thelma Todd's Death - Solved! Marvinjwolf.com. Retrieved August 9, 2025, from https://www.marvinjwolf.com/blog/thelma-todds-death-solved