The Mad Butcher of Kingsbury Run: Hunting Cleveland’s Phantom Torso Killer

Amid the Great Depression, a killer terrorized Cleveland, leaving a trail of dismembered bodies. Famed lawman Eliot Ness hunted a ghost, and the city's most horrifying case went cold.

Cleveland was a city on its knees in the mid-1930s. The Great Depression hadn’t just knocked on the door; it had kicked it in, leaving half the city’s population jobless. Thousands were crammed into sprawling, desperate shantytowns built from scrap metal and despair. The city was already suffocating.

Then, someone decided to start cutting off heads.

Between 1934 and 1938, a new kind of horror began to stalk the city’s grimy margins. This wasn’t just murder. It was a gruesome campaign of meticulous butchery. At least twelve people - men and women from the city’s most forgotten corners - were killed, decapitated, and then dismembered with a chilling, surgical precision. Their remains were scattered across Kingsbury Run, turning a symbol of public misery into a private, monstrous gallery. The press, with its knack for lurid titles, called the killer the “Mad Butcher.”

This nightmare case landed squarely in the lap of Eliot Ness. Yes, that Eliot Ness. Fresh off the international fame of busting Al Capone, he was Cleveland’s new Public Safety Director, a bona fide American hero hired to clean up the city. Ness was a master at dismantling criminal organizations through relentless investigation and prosecution.

But this was different. He wasn’t fighting the mob; he was hunting a ghost.

The man who took down Capone was now faced with a “scientific” killer, a phantom who left behind expertly dissected bodies but no witnesses, no motives, and no traditional clues. Ness was about to descend into one of the most frustrating and horrifying manhunts in American history, chasing a new breed of monster who seemed to be rewriting the rules of murder itself.

The City of Fear & The Nameless Dead

The Mad Butcher’s greatest accomplice wasn’t a person. It was the city of Cleveland itself.

Before the crash, Cleveland was a powerhouse. The fifth-largest city in America, a booming hub of steel and auto parts. It was a place so ambitious that it built the second-tallest building in the country, the Terminal Tower, just for the bragging rights. But that prosperity was built on a fragile foundation of heavy industry. When the economy finally collapsed, Cleveland fell. Harder and faster than most.

By 1933, the numbers were staggering. A full 50% of the city was out of work. This wasn’t just a recession; it was a social catastrophe. Charities were swamped. Evictions became a daily spectacle. People who once had steady factory jobs now had nowhere to go. So, they built a new city inside the old one. In the desolate ravine of Kingsbury Run, sprawling shantytowns - “Hoovervilles” - rose from the mud. Hundreds of men and women lived in cramped conditions, packed into shacks made of scrap wood, tin, and cardboard.

It was a city of ghosts. The residents of these shantytowns were completely invisible. They had no permanent addresses, no family ties, no official records. They lived off the grid. If one of them vanished, who would know? The Great Depression had created the perfect victim pool for a predator: a steady supply of anonymous people whose disappearance wouldn’t make a sound.

The killer’s methods were as grim as the city he stalked. His signature was a grotesque pattern of violence, repeated with terrifying consistency.

First, decapitation. Often, this was the actual cause of death. The cuts were clean, precise. This wasn’t the work of a frenzied amateur; it was the work of someone with a surgeon’s skill and a deep, practical knowledge of human anatomy. Male victims were almost always emasculated. Some bodies were even treated with a chemical that turned the skin reddish and leathery, a final act of desecration that made them nearly impossible to identify.

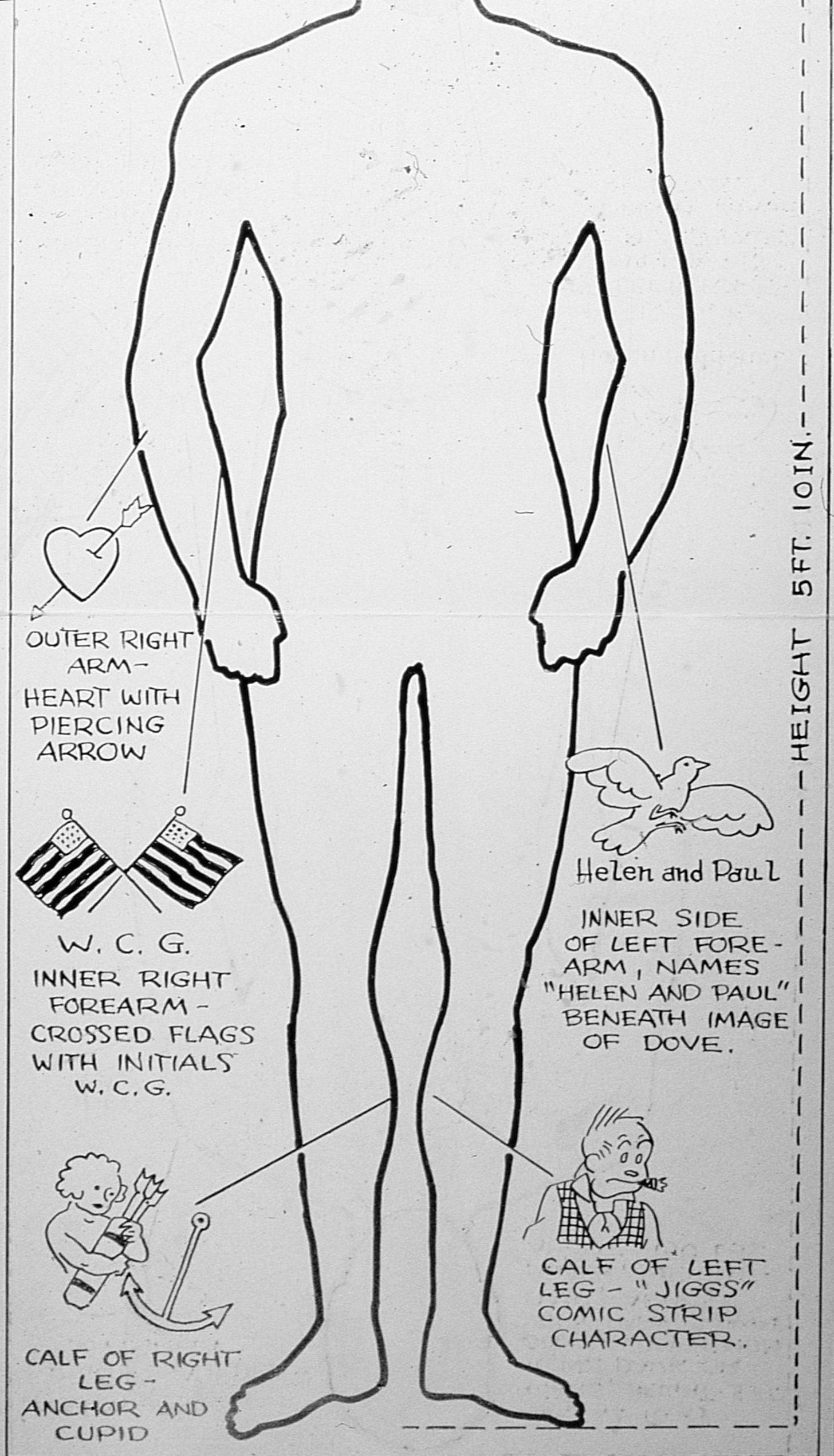

The first official victim appeared in September 1935. Edward Andrassy and another unidentified man were found near Jackass Hill in Kingsbury Run, their headless bodies left for the world to see. Andrassy was only identified by old fingerprints. Most weren’t so lucky. From Florence Polillo, whose body was packed into baskets, to the “Tattooed Man,” the victims were a parade of the nameless dead. The police faced an impossible task. How do you identify people who were, in a sense, already missing long before the killer ever found them?

The Untouchable vs. The Butcher

Into this fog of misery and murder strode a living legend. Eliot Ness arrived in Cleveland in late 1935 with a halo of celebrity still glowing around him. This was the man who faced down Al Capone and his army of thugs in Chicago. The press called him “The Untouchable,” the incorruptible G-man who couldn’t be bought or broken. Mayor Harold Burton hired him to be the city’s new Public Safety Director, and his mission was simple: clean up Cleveland’s notoriously corrupt police and fire departments.

And for a while, he was wildly successful. Ness was a reformer, not a beat cop. He attacked the city’s problems with systematic precision. He fired corrupt officials, established a modern police academy, and equipped his force with the latest technology, like two-way radios in patrol cars. The results were stunning. Within 18 months, Cleveland’s overall crime rate dropped by 25%. The Untouchable was living up to his own hype.

Then the bodies started piling up in Kingsbury Run.

Hunting the Mad Butcher was a challenge Ness was uniquely unsuited for. His entire career was built on taking down criminal organizations. He knew how to follow money trails, flip informants, and prosecute complex conspiracy cases. But the Butcher wasn’t an organization. He was a phantom. A lone, psychologically-driven killer who left no witnesses, no accomplices, and no obvious motive. Ness was a master chess player who suddenly found himself in a street fight with a ghost.

The investigation he launched was massive, the largest in the city’s history. Detective Peter Merylo and Martin Zelewski became the ground troops in this war, immersing themselves in the grim world of the Roaring Third vice district and the Hoovervilles of the Run. They went undercover, interviewed thousands of people, and chased down every dead-end lead imaginable. But brute force wasn’t enough.

They had to get creative. Desperate, even.

In June 1936, they found the head of Victim #4, the “Tattooed Man.” The man had six very distinctive tattoos, which should have made for a quick identification. But nobody came forward. So, the investigators tried something straight out of a horror movie. They made a plaster death mask of the man’s head. And then, in a move that feels both brilliant and profoundly ghoulish, they put the mask and a chart of his tattoos on public display at the Great Lakes Exposition - a massive fair on Cleveland’s lakefront, their version of the World’s Fair.

Think about that for a second. Tens of thousands of families, there for a fun day out, were invited to gaze upon the face of a dead man in the hope that someone, anyone, might recognize him. Over 100,000 people saw the grim exhibit. Not a single one could give him a name. The killer wasn’t just choosing his victims from the margins; he was choosing people who were so completely erased from society that not even a public spectacle could bring their identity back from the dead. Ness and his men weren’t just fighting a killer; they were fighting total human anonymity.

A Tale of Two Suspects

As the years dragged on and the body count climbed, the investigation finally zeroed in on two primary suspects. But these weren’t just two potential killers; they were men from opposite ends of the social spectrum. Their stories reveal just how much class and connections mattered in 1930s America, and how justice wasn’t always blind - sometimes, it actively peeked. The handling of these two men tells a story as dark as the murders themselves.

The Secret Suspect: Dr. Francis Sweeney

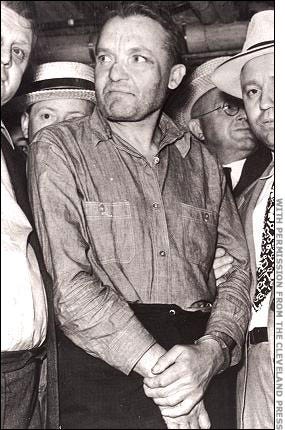

The man Eliot Ness privately became convinced was the Mad Butcher wasn’t some shifty transient from the shantytowns. He was a doctor. Dr. Francis E. Sweeney was a talented surgeon who had served in a medical unit during World War I, where he had the grim job of performing field amputations. The war broke something in him. He came home suffering from severe depression and anxiety, which he treated with a cocktail of alcohol and drugs.

The circumstantial evidence against him was damning. He had the surgical skill to perform the precise dismemberments. He was known to frequent the vice districts and seedy bars where the killer likely found his victims. And, most importantly, he was related to a sitting US Congressman, Martin L. Sweeney - a man who happened to be one of Eliot Ness’s most vocal political enemies. Talk about a complication.

In 1938, Ness had Sweeny secretly taken into custody. This wasn’t a backroom beating at the local precinct. This was a ten-day interrogation held in a private hotel room. Ness subjected Sweeney to two of the earliest polygraph tests, and according to the examiner, Sweeney failed them both spectacularly. The examiner allegedly told Ness he was sure he had the killer.

But Ness was in a bind. He had a mountain of circumstantial evidence and a failed lie detector test, but not a single piece of hard, physical proof that would stand up in court. And he knew that charging the cousin of a powerful congressman without an airtight case would be professional suicide.

So, he let him go.

Dr. Sweeney was never formally charged. Shortly after his secret interrogation, he voluntarily committed himself to a veterans’ hospital. And right after he was institutionalized, the canonical Torso Murders stopped. Cold. As a final, chilling cherry on top, Sweeney spent the rest of his life mailing taunting, threatening postcards to Ness and his family. They only stopped when Sweeney died in 1964.

The Scapegoat: Frank Dolezal

In a stark contrast to the well-connected doctor was Frank Dolezal. Dolezal was a 52-year-old immigrant bricklayer with a bad reputation who had briefly lived with one of the victims, Florence Polillo. In the summer of 1939, nearly a year after the last murder, the Cuyahoga County Sheriff’s Department - looking to close the books on at least one of the killings - arrested him.

Dolezal was not interrogated in a hotel room. After a long and brutal session with sheriff’s deputies, he confessed to killing Polillo. But he recanted almost immediately, claiming he’d been beaten until he said what they wanted to hear.

A little over a month later, Frank Dolezal was found dead in his jail cell. He was hanging from a hook by a piece of his own shirt. The official cause of death was ruled a suicide.

The story should have ended there, but Dolezal’s family didn’t buy it. They demanded a second, independent autopsy. And what it revealed was horrifying. Dolezal had six broken ribs and a host of other injuries that were clearly not self-inflicted and absolutely inconsistent with death by hanging. The evidence strongly suggested his confession had been tortured out of him, and his “suicide” was, at best, a cover-up for a fatal beating.

Even Eliot Ness never seriously believed Dolezal was the real killer.

You couldn’t ask for a clearer picture of the two-tiered justice system. The educated doctor with political ties got a secret interrogation and a quiet exit. The poor immigrant laborer got a brutal interrogation, became a public scapegoat, and died violently in a jail cell.

A Cold Case and a Dark Legacy

By August of 1938, Eliot Ness was out of leads and out of patience. The pressure on him was immense. For nearly three years, a monster had been leaving dismembered bodies all over his city, and the country’s most famous cop couldn’t do a thing to stop him. The final straw came on August 16th, when the remains of the last two victims were discovered in a city dump, directly in view of Ness’s own office window at City Hall. It was a brazen, personal taunt.

Ness snapped.

Two days later, he personally led a raid on the Kingsbury Run Shantytowns. He and 35 officers swept through the encampments, arresting 63 men. Then, in a legally dubious act of pure frustration, Ness ordered the shacks to be torched. He burned the entire Hooverville to the ground. His public rationale was that he was eliminating the killer’s hunting ground and victim pool. But everyone saw it for what it was: a desperate, heavy-handed admission of failure. The Untouchable had been beaten, and now he was salting the earth.

After that, the case just… went cold. The trail of breadcrumbs ended. The official murders stopped, and with no direct evidence against Sweeney and no new leads, the investigation stalled. The Butcher had outplayed them, thanks in large part to the era’s technology. Without DNA analysis, advanced serology, or computerized databases, investigations were fighting a modern monster with old-fashioned tools. A phantom killer with surgical skills was simply a foe that 1930s forensics couldn’t catch.

But the story doesn’t quite end there. Like all great unsolved mysteries, the case has a dark legacy, a half-life of lingering questions and chilling possibilities. For decades, researchers and armchair detectives have debated key aspects of the case. How many victims were there, really? The official count was twelve, but many, including the Cleveland Police Museum, count a thirteenth, the “Lady of the Lake” from 1934. Lead detective Peter Merylo believed the killer’s spree might have started in the 20s and stretched into the 50s, including similar dismemberment murders in Pennsylvania.

And then there’s the most tantalizing “what if” of all: the possible connection to the Black Dahlia. In 1947, the body of Elizabeth Short was found in Los Angeles, cut in half with surgical precision in a way eerily similar to some of the Mad Butcher’s victims. A popular theory, championed by former LAPD detective Steve Hodel, suggests that his father, Dr. George Hodel, was the killer in both cases. While it’s a speculative leap, the parallels in the gruesome M.O. are hard to ignore.

Ultimately, the Butcher faded back into the shadows, leaving behind a legacy of terror and a set of a dozen horrifying, unsolved murders that still stand as one of America’s greatest and darkest criminal mysteries.

The Shadow in the Archives

In the end, the scariest thing about the Mad Butcher isn’t just what he did. It’s that he could exist at all. He was a monster born from a specific moment in time, a predator perfectly adapted to his environment. The Great Depression didn’t just create poverty; it created anonymity on an industrial scale. It erased people. And in that void, the killer found his freedom.

For four years, he moved through a major American city like a ghost, hunting those who had already been forgotten. He turned human beings into forensic puzzles and left them on the doorstep of the nation’s most celebrated lawman, a personal challenge from a foe who had no name, no face, and no traceable motive. Eliot Ness, the man who stared down the mob, was left chasing a shadow, his every move countered by a killer who seemed to operate outside the known rules of crime.

The case file on the Cleveland Torso Murders remains open, but it’s a cold, quiet file. The leads are long dead. The primary suspect is gone. The victims, many of them, still just names on a coroner’s report, their full stories lost to the decay of the era. The Butcher wasn’t just a serial killer; he was a symptom of a societal collapse, a man who understood that in a city full of invisible people, a murderer could be invisible, too. He walked out of the chaos, committed his atrocities in plain sight, and then, when he was done, simply faded away, leaving nothing behind but a scar on a city’s soul and one of history’s most perfect, horrifying mysteries.

Thanks for joining me in the archives for this case. If this story chilled you to the bone, share it with a friend who loves a good mystery.

And if you want to discuss the theories, suspects, and lingering questions, upgrade to a paid subscription to join the conversation in the comments!

References

Associated Press. (1938, August 17). Two more slain in Cleveland's jigsaw murders; Both found in dump heap near city hall. The New York Times.

Associated Press. (1938, August 19). Shanties are burned in hunt for slayer. The New York Times.

Associated Press. (1939, August 25). Torso case prisoner ends life in cell. The New York Times.

Badal, J. J. (2001). In the wake of the butcher: Cleveland's torso murders. The Kent State University Press.

Badal, J. J. (2010). Though murder has no tongue: The lost victim of Cleveland's mad butcher. The Kent State University Press.

Badal, J. J. (2013). Hell's wasteland: The Pennsylvania torso murders. The Kent State University Press.

Badal, J. J. (2014). In the wake of the butcher: Cleveland's torso murders (Expanded ed.). The Kent State University Press.

Bellamy, J. S. (1966). The man in the pin-stripe suit. A. A. Wyn.

Black, L. (2018). Eliot Ness and the mad butcher: Hunting a serial killer at the dawn of modern criminology. University of Illinois Press.

Case Western Reserve University. (n.d.-a). Ness, Eliot. In Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. Retrieved September 6, 2025, from https://case.edu/ech/articles/n/ness-eliot

Case Western Reserve University. (n.d.-b). Public safety. In Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. Retrieved September 6, 2025, from https://case.edu/ech/articles/p/public-safety

Case Western Reserve University. (n.d.-c). Torso murders. In Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. Retrieved September 6, 2025, from https://case.edu/ech/articles/t/torso-murders

Cleveland Plain Dealer. (1936, June 6). Head found in run is sixth torso case.

Cleveland Plain Dealer. (1938, August 17). Two more slain in torso murders.

Cleveland Police Museum. (n.d.). Collections: Torso murders. Retrieved September 6, 2025, from https://www.clevelandpolicemuseum.org/collections/torso-murders/

DeMarco, L. (2020, October 29). The Cleveland Torso Murderer: The scariest unsolved serial killer case you've never heard of. Cleveland.com.

Eayerth, T. (n.d.). The Kingsbury Run murders. Hideous Crimes.

Gerber, S. R. (1947). The scientific investigation of the torso murder cases. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 38(3), 314–327.

Guerrieri, V. (2021, October 28). Eliot Ness’s unsolved Cleveland Torso Murders. Belt Magazine.

Heimel, P. (2021). Eliot Ness: The real story. Knox Books.

Hodel, S. (2003). Black Dahlia avenger: The true story. Arcade Publishing.

Krajicek, D. J. (n.d.). The mad butcher of Kingsbury Run. Crime Library.

Lytle, A. (2022, October 28). Unsolved: Who was the Cleveland Torso Murderer? WKYC Studios.

Monroe, D. (2017). The depraved: The shocking true story of America's first serial killer. WildBlue Press.

Newton, M. (2009). The encyclopedia of unsolved crimes. Facts On File.

Nickel, S., & Derfner, D. (2019). Torso: A true crime graphic novel. Harry N. Abrams.

Perry, D. (2006). Eliot Ness: The rise and fall of an American hero. Viking Adult.

The Akron Beacon Journal. (1938, August 18). Ness raids shantyville in torso hunt.