The Vanishing Judge: A Story of Corruption, Secrets, and a Showgirl

Before he disappeared, Judge Joseph Force Crater lived a double life in the heart of a rotten city. Explore the scandal that led to him becoming "the missingest man in New York."

On the hot, sticky evening of August 6th, 1930, a New York Supreme Court Justice named Joseph Force Crater did something truly remarkable: he stepped out of a restaurant on a busy Manhattan street and simply ceased to exist. One minute, he was a man in a sharp suit and a Panama hat, smiling at his dinner companions; the next, he was a ghost, a legend, and one of the most baffling mysteries in American history.

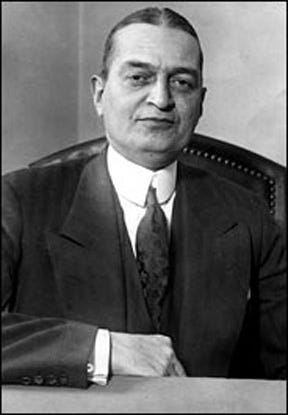

You have to understand, this wasn’t just some random guy. Crater was a big deal. He’d been appointed to the bench just four months earlier by the governor, Franklin D. Roosevelt. He was also a professor, a member of society, and a well-connected figure within Tammany Hall—the notoriously corrupt political machine that effectively controlled New York City. But he was also “Goodtime Joe,” a man leading a carefully constructed double life, complete with a showgirl mistress and a deep familiarity with the city’s speakeasies.

In 1930s New York, a city drowning in corruption and about to be scrubbed clean by the famous Seabury Commission investigations, a man like that disappearing wasn’t just a missing persons case; it was a political earthquake. The investigation itself was a mess from the start, hampered by a nearly month-long delay before anyone even called the police. When a grand jury was finally convened, they heard testimony from 95 people and essentially threw their hands up, unable to determine if Crater was dead, had amnesia, or had simply walked away.

So what really happened to the judge? Was he silenced by his powerful friends? Taken out by the mob over a debt? Or did this brilliant legal mind, seeing the walls closing in, orchestrate the perfect exit? The story is a tangled web of politics, crime, and secrets, and it all starts on that single, fateful night. Let’s get into it.

The Scene & The Victim: A Judge, a Showgirl, and a Street Full of Secrets

New York City in 1930 was a city of dizzying contradictions. The Great Depression was tightening its grip, yet the champagne-soaked glamour of the Jazz Age refused to die. Prohibition was the law of the land, which, in practice, just meant that the criminal underworld had built a booming empire on bootlegging, speakeasies, and gambling. And overseeing it all was Tammeny Hall, the Democratic Party’s political machine, a corrupt and powerful beast that controlled nearly everything in the city, especially the judiciary. This was a world where mobsters, politicians, and judges all drank at the same bars, a place where the lines between law and crime were hopelessly, purposefully blurred. This was the world of Joseph Force Crater.

On paper, Judge Crater was the pinnacle of respectability. Born in Pennsylvania, he was armed with degrees from Lafayette College and Columbia Law School. He was a successful lawyer and a respected law professor at both Fordham and NYU. His political career was thriving; as president of the Tammany-aligned Cayuga Democratic Club, he was the protege of the powerful US Senator Robert F. Wagner. But that was only one side of the man. To his friends, he was “Goodtime Joe,” a dapper fixture of Broadway’s nightlife with a well-known fondness for the company of showgirls. He was a man living two lives, and the strain of keeping them separate was beginning to show.

Which brings us to the night of August 6th. Crater’s evening plans seemed social enough. He bought a single ticket to a new comedy, Dancing Partner, playing on West 44th Street. He then headed to dinner at Billy Haas’s Chophouse, a popular spot at 332 West 45th Street. He wasn’t alone. He was joined by his friend and lawyer, William Klein, and a 22-year-old showgirl named Sally Lou Ritz - the same woman he’d been seen with in Atlantic City just days earlier. By all accounts, the dinner was perfectly normal. Crater was jovial and seemed unconcerned that the curtain had already gone up for the show he supposedly had a ticket for.

Around 9 PM, the trio walked out of the restaurant onto the bustling street. And it’s here, at the literal curb, that the entire case fractures. The story that William Klein and Sally Lou Ritz first told the police was simple: Judge Crater saw a taxi, hailed it, waved a cheerful goodbye from the window with his Panama hat, and was driven away, heading west. A clean, simple exit. The problem? They both later retracted that story. In their new version, they were the ones who got in the cab, leaving the judge standing alone on the sidewalk. The official investigation would later conclude, in a masterpiece of unhelpful understatement, that the original taxi story was “determined to be mistaken.”

Mistaken or not, one fact remained. Whether he was in a phantom taxi or was left standing on the street, Judge Joseph Force Crater was never seen again.

The Investigation: A Cold Trail & a Secret Drawer

For an investigation to work, it has to, you know, start. The single most significant problem in the Crater case was the nearly four-week delay before anyone officially reported him missing. His life was so perfectly compartmentalized that no one sounded the alarm. His wife, Stella, was at their summer cabin in Maine. She got annoyed when he missed her birthday on August 9th, but she was used to his business trips and figured he was just tied up. Meanwhile, his colleagues back in New York, including his partners at his prestigious law firm, assumed he was still enjoying his vacation up in Maine. It wasn’t until August 25th, when he failed to show up for the opening of the courts, that his fellow justices realized something was seriously wrong.

But even then, they didn’t call the police. Of course not. That would create a scandal. Instead, these powerful men, likely wanting to protect their patron Senator Wagner, launched their own “discreet’ private probe. It wasn’t until that failed completely that his law partner, Simon H. Rifkind, finally walked into police headquarters on September 3rd and filed a missing persons report. By then, the trail was 28 days old. Any potential crime scene was long cold, any witnesses’ memories had faded, and any tracks - left by Crater or his enemies - were gone.

While his friends and family were in the dark, Crater himself had been a whirlwind of methodical, suspicious activity on August 6th. He spent two hours in his courthouse chambers, where his law clerk later reported he destroyed a large number of documents. Around noon, he sent the same clerk, Joseph Mara, to cash two checks totaling $ 5,150—a massive sum at the time. Then, he had Mara help him transport two locked briefcases and several portfolios of papers to his apartment on Fifth Avenue. The man was clearly preparing for something big.

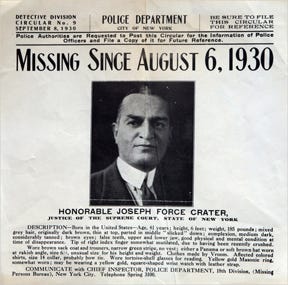

Once the news finally broke, it exploded onto the front pages, transforming the missing judge into a national sensation. The press dubbed him “the missingest man in New York,” a title that would stick forever. The police, facing an impossible task, posted a $5,000 reward, which only resulted in thousands of false sightings. Their official line, at least initially, was to float the idea of amnesia - a theory so flimsy it was almost insulting.

But the case’s most bizarre twist was yet to come. On January 20, 1931, months after the disappearance, Stella Crater was going through her husband’s things in their apartment. In a dresser drawer that police had previously searched and found empty, she discovered several envelopes. The contents were stunning. There was $6619 in cash, various stocks and bonds, and life insurance policies worth $30,000. And then there was a short, handwritten note. It contained a list of people who owed the judge money and ended with a hauntingly ambiguous line: “Am very weary. Love, Joe.” This discovery blew the “planned escape” theory full of holes. Why would a man running for his life take $5,150 but leave behind an even larger sum of cash and all his financial securities? The crucial documents from those locked briefcases, however, weren’t among the items. They have never been found.

The Rougues’ Gallery of Suspects

Suspect #1: The Judge Himself

Occam’s Razor tells us the simplest explanation is usually the correct one. And on the surface, the idea that Judge Crater orchestrated his own escape is the simplest theory of all. The man was in trouble; he knew it, and he decided to get out of town before the walls caved in. The evidence for a planned escape is so strong, it almost feels like a checklist for a man about to go on the run.

First, he spent hours destroying documents in his courthouse chambers. You don’t do that unless you’re erasing a trail. Second, he liquidated assets, cashing checks for $ 5,150 in cash—a huge amount of untraceable money for 1930. Third, he had his safe deposit box completely emptied. And finally, he had a known double life, complete with a showgirl mistress, providing the perfect narrative for a man ditching his responsibilities to start fresh somewhere new. Faced with possible indictment in the looming Seabury investigations into Tammany Hall, “pulling a Crater” seems like a perfectly logical move.

But here’s where this clean, simple theory completely falls apart under the weight of one inconvenient fact: the stuff he left behind.

Think about the bombshell discovery Stella Crater made in that “secret” dresser drawer. A man planning a new life takes his nest egg with him. Yet Crater left behind $6619 in cash - more than the amount he took - along with valuable stock certificates, bonds, and his life insurance policies naming Stella as the beneficiary. Who packs for a new life by taking a bundle of cash but leaving a bigger bundle and his entire financial portfolio behind? These aren’t the actions of a man escaping; they’re the actions of a man putting his affairs for his own death.

Furthermore, if he ran away with his mistress, he did a terrible job of it, because Sally Lou Ritz didn’t go anywhere. Police found her a short time later in Ohio, claiming she was home caring for her sick father. For a man as famous and recognizable as Judge Crater to live out the rest of his life in total anonymity, without a single credible sighting in the decades to follow, strains belief to the breaking point.

So the planned escape theory, as neat as it seems, doesn’t hold water. It explains some of his actions, but it completely ignores the others, leaving us with the central paradox of a man who seemed to be preparing for two opposite futures simultaneously.

Suspect #2: The Political Machine

For decades, New York City was run by Tammany Hall, the formidable Democratic Party political machine that controlled nearly every facet of municipal life. And in 1930, the machine was in a panic. Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt had authorized a sweeping investigation into the city’s corruption, led by a highly respected former judge named Samuel Seabury. The Seabury Commission was tearing through Tammany’s web of graft, and Judge Crater was sitting right at the center of the spider’s web.

The investigation’s ground zero was the corrupt appointment of a man named George Ewald to a judgeship. As it happens, Judge Crater, as president of his local Democratic club, had been the toastmaster at the dinner celebrating that very appointment, linking him directly to the scandal. He was a man who knew too much. He knew how the machine worked, who paid for their judgeships, and where all the bodies were buried - figuratively, of course. A subpoena for him to testify could have brought down the entire organization, from Mayor Jimmy Walker to potentially even Crater’s powerful mentor, US Senator Robert F. Wagner. In the cutthroat world of Tammany politics, that made him a profound liability.

If there was any doubt about the stakes, they were made brutally clear just a few months later with the murder of Vivian Gordon. Gordon, a prostitute and blackmailer, had offered to testify before the Seabury Commission about police graft. Five days later, she was found strangled in a Bronx park. The message was unmistakable: if you talk, you die. For a man like Judge Crater, who was deeply enmeshed in the system under investigation, this wasn’t a threat; it was a promise.

This is the theory that many serious researchers, like author Stephen Riegel, find most plausible. It suggests that Crater saw the writing on the wall and was preparing to flee (which explains the cash and destroyed documents), but his political “associates” got to him before he could make a run for it. They couldn’t risk him being caught and forced to testify, so they silenced him permanently. It’s a clean, compelling narrative that accounts for both his strange preparations and his ultimate disappearance.

The only problem? It’s built entirely on circumstantial evidence. No confession, no insider testimony, and no physical proof has ever emerged to link any Tammany official to a murder plot directly. It’s a powerful and logical theory, but it remains just that - a theory.

Suspect #3: The Mob

The line between a Tammany Hall politician and an organized crime figure in 1930 was, to put it mildly, blurry. They needed each other to thrive, and Judge Crater, in his pursuit of the high life, moved comfortably in a world frequented by both. This theory suggests he wasn’t silenced for what he knew, but killed for a more personal offense against the city’s criminal underworld. The potential motives read like a noir novel: a gambling debt he couldn’t pay, a business deal gone sour, or a dispute with a gangster over a woman. There was even a story, pushed by Stella Crater’s lawyer, that a showgirl named June Brice was blackmailing the judge, and her gangster boyfriend had him killed. Like most mob theories, however, it suffers from a frustrating lack of specifics. While Crater definitely swam in mob-infested waters, there’s no direct proof of a conflict that would escalate to murdering a Supreme Court Justice.

A more elegant and intriguing variation of this theory is “death by misadventure.” Championed by author Richard Tofel, it posits that Crater didn’t intend to disappear at all. The theory goes that he died of natural causes, likely a heart attack, in a very compromising position - specifically, inside the city’s most famous brothel, run by the notorious madam Polly Adler. For Adler, a dead judge in her establishment would be a business-ending catastrophe, implicating her powerful clientele. So, what do you do? You call your mob contacts - men like Dutch Schultz or Lucky Luciano - who make the body disappear, quietly and efficiently. This would explain everything: the lack of a body, the confusion, and even why the notoriously corrupt NYPD of the era might not have pursued the case with much enthusiasm.

It’s a tidy explanation that fits neatly. There’s just one problem. The entire theory rests on a persistent rumor that an early draft of Polly Adler’s memoir contained this story, but that it was scrubbed from the final version. That manuscript has never been produced. So, like the other mob theories, it remains a tantalizing piece of folklore—a plausible, yet utterly unproven, scenario.

Suspect #4: The Crooked Cop

In 2005, the public learned of a letter written years earlier by a woman named Stella Ferrucci-Good, with instructions that it be opened only after her death. Her late husband had been an NYPD detective, and according to her letter, he knew the secret of Judge Crater’s fate. She claimed her husband told her that Crater had been murdered by a corrupt cop named Charles Burns, who also worked as a bodyguard for a Murder, Inc. hitman, and Burns’s brother, Frank, who was a taxi driver. The letter even named the burial spot: under the Coney Island boardwalk, near West Eighth Street, at the exact location where the New York Aquarium now stands.

At first glance, this is it. The perfect solution. It’s specific, it names names, and it brilliantly resolves the mystery of the conflicting taxi testimony from the night of the disappearance. Of course, William Klein and Sally Lou Ritz were confused about the taxi - it wasn’t a random cab, it was part of the hit, driven by one of the killers. It’s a story that ties up nearly every loose end in a neat little bow.

Too neat, as it turns out. The theory is incredibly compelling, but it falls apart under the weight of one inconvenient bit of construction history. The New York Aquarium was built in the 1950s, and the construction required extensive excavation of that very site. Researchers who have checked the records from that time have found no reports of any human remains being discovered. It’s hard to believe that a construction crew could dig up the foundation for a massive aquarium and somehow miss a 20-year-old skeleton buried right under their feet.

Because of this glaring problem, most experts on the case, including author Richard Tofel, are deeply skeptical. The “Coney Island Confession” is a fantastic story, but it’s likely just another fascinating, frustrating dead end in a case full of them.

A Legal Ghost & an American Legend

With a cold trail and a suspect list full of powerful men, the official investigation sputtered to an ignominious end. In October 1930, a grand jury was convened to get to the bottom of the mystery. It heard from 95 different witnesses, including Crater’s law partners, his clerks, and his friends, but conspicuously, not his wife, Stella, who refused to appear. After compiling nearly a thousand pages of testimony, the jury was forced to issue what might be the most unsatisfying conclusion in legal history, stating that “the evidence is insufficient to warrant any expression of opinion as to whether Crater is alive or dead… or is the victim of a crime.” It was an official, institutional shrug. The system had failed.

For Stella Crater, the verdict was a nightmare. She was now the wife of a man who legally wasn’t dead, but was most certainly gone. She faced severe financial hardship, losing their lavish Fifth Avenue apartment and, at one point, taking a job as a telephone operator for just $12 a week. For nine long years, she fought to have her husband declared legally dead, finally succeeding on June 6, 1939, which allowed her to collect on his life insurance policy. She eventually remarried, and in 1961, she published a memoir, The Empty Robe, her final attempt to control the narrative. In it, she vehemently denied the widespread reports of his infidelity and insisted her husband was a devoted man murdered by a corrupt political machine.

And what of the other woman in this story, the showgirl Sally Lou Ritz? She proved to be the savviest of them all. Shortly after the case became a media circus, she left New York and was located by police in Youngstown, Ohio. After that, she disappeared from the public record for decades, leading some to list her as a missing person herself. But information that surfaced years later revealed the truth: she had changed her name, married, and lived a full, quiet life, never once speaking of her connection to the infamous case.

While the key players moved on or faded away, Judge Crater achieved a strange kind of immortality. His name became a part of the American language. “To pull a Crater” became a common slang expression for taking an unauthorized leave or disappearing suddenly. And for decades, nightclub comedians and pranksters with access to a public address system had a go-to punchline: “Judge Crater, call your office.” Before there was Jimmy Hoffa, the 20th century’s icon of mysterious disappearances was a dapper, corrupt, and utterly gone New York City judge.

The Paradox of the Missingest Man

So, where does that leave us? For nearly a century, historians, detectives, and armchair sleuths have attempted to neatly solve the disappearance of Judge Joseph Force Crater, but no single theory has ever gained traction. The reason is simple: the judge himself. His final actions were a masterclass in contradiction, a paradox that is at the very heart of the mystery. On the one hand, he behaved like a man meticulously planning to flee, destroying documents and gathering a large sum of untraceable cash. On the other hand, he acted like a man preparing for his death - leaving behind an even larger sum of money, valuable securities, and his life insurance policies for his wife to find.

A man running away takes his fortune with him. A man expecting to be murdered doesn’t bother gathering getaway cash. Crater did both. This profound ambiguity suggests the truth isn’t a simple case of “Did he flee or was he murdered?’ but something far murkier. He was likely preparing for a desperate, high-stakes transaction - a blackmail payment, a bribe, a final confrontation - from which he hoped to escape, but knew he might not return.

Ultimately, the question of what happened to one man may be less important than what his disappearance revealed about the world he inhabited. Judge Crater wasn’t just a person; he was a symptom of a system on the verge of collapse. The very corruption of Tammany Hall that had facilitated his rise also created the perfect conditions for his fall. His vanishing act became a powerful symbol of that rot, fueling the public outrage that empowered reformers and helped dismantle the world that had both made and destroyed him. He was a ghost in the machine, and his absence helped bring the whole thing crashing down.

References

Abbott, K. (2012, August 24). The dead woman who brought down the mayor. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-dead-woman-who-brought-down-the-mayor-27003776/

Ancient and Esoteric Order of the Jackalope. (n.d.). Judge Crater, call your office. Retrieved July 25, 2025, from https://order-of-the-jackalope.com/call-your-office/

Bray, S. L. (2010). Preventive adjudication. University of Chicago Law Review, 77(3), 1275.

Crater, S. W., & Fraley, O. (1961). The empty robe. Doubleday.

The Doe Network. (n.d.). Case file 840DFNY. Retrieved July 25, 2025, from https://www.doenetwork.org/cases/cases/840dfny.html

EBSCO. (n.d.). Crater disappearance. EBSCO Research Starters. Retrieved July 25, 2025, from https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/history/crater-disappearance

EBSCO. (n.d.). Organized crime in the 1930s. EBSCO Research Starters. Retrieved July 25, 2025, from https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/history/organized-crime-1930s

Ephemeral New York. (2008, October 6). Judge Crater: the missingist man in America. https://ephemeralnewyork.wordpress.com/2008/10/06/judge-crater-the-missingist-man-in-america/

Federal Bureau of Investigation. (n.d.). Joseph Force Crater. FBI Records: The Vault. Retrieved July 25, 2025, from https://vault.fbi.gov/Joseph%20Force%20Crater

Find a Grave. (n.d.). Joseph Force Crater (1889-1930). Retrieved July 25, 2025, from https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/6984692/joseph_force-crater

Goodreads. (n.d.). The Empty Robe: The Story of the Disappearance of Judge Crater. Retrieved July 25, 2025, from https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/8458743-the-empty-robe

Historic Newspapers. (n.d.). A year in history: 1930 timeline. Retrieved July 25, 2025, from https://www.historic-newspapers.com/blogs/article/1930-timeline

Historical Society of the New York Courts. (n.d.). Samuel Seabury. Retrieved July 25, 2025, from https://history.nycourts.gov/biography/samuel-seabury/

HISTORY.com Editors. (2025, May 28). Judge Joseph Force Crater becomes the "missingest man" in New York. HISTORY. Retrieved July 25, 2025, from https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/august-6/joseph-force-crater-becomes-the-missingest-man-in-new-york

Hohl, K. (2023, May 11). Judge Crater, call your office: The curious disappearance of a prohibition-era judge. Something is Going to Happen. https://somethingisgoingtohappen.net/2023/05/11/judge-crater-call-your-office-the-curious-disappearance-of-a-prohibition-era-judge-by-kate-hohl/

Indianapolis Times. (1937, August 6). Page 14. Hoosier State Chronicles.

https://newspapers.library.in.gov/?a=d&d=IPT19370806.1.14

Kershner, K. (2017, August 4). Decades later, the disappearance of Judge Joseph Force Crater remains a mystery. HowStuffWorks. https://history.howstuffworks.com/history-vs-myth/decades-later-disappearance-judge-joseph-force-crater-remains-mystery.htm

Lafayette College. (2011, April 14). Looking back: New novel suggests fate of Judge Joe Crater, Class of 1910. Lafayette News. https://news.lafayette.edu/2011/04/14/looking-back-new-novel-suggests-fate-of-judge-joe-crater-class-of-1910/

Lawhon, A. (2015, January 8). Case closed: the true story of a happy ending. Ariel Lawhon. https://www.ariellawhon.com/2015/01/08/case-closed-the-true-story-of-a-happy-ending/

Marriott, M. (2022, October 28). The Lafayette alum who became the ‘missingest man in America’. The Lafayette. https://lafayettestudentnews.com/138299/culture/the-lafayette-alum-who-became-the-missingest-man-in-america/

New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. (2013, October 29). Tammany Hall, 100 East 17th Street (LP-2490). https://s-media.nyc.gov/agencies/lpc/lp/2490.pdf

NY Press. (2018, September 6). The missingest man in New York. https://www.nypress.com/news/the-missingest-man-in-new-york-LBNP1020020625306259995

Old NY Tours. (n.d.). Judge Crater Declared Dead. Retrieved July 25, 2025, from http://www.oldnytours.com/on-this-day-in-old-new-york/judge-crater-declared-dead

Riegel, S. J. (2022). Finding Judge Crater: A life and phenomenal disappearance in Jazz Age New York. Syracuse University Press.

Schlam Stone & Dolan LLP. (2004, December 4). Lawyers' bookshelf: Vanishing Point: The Disappearance of Judge Crater and the New York He Left Behind. https://www.schlamstone.com/media/publications/2004-12-04-lawyers-bookshelf-vanishing-point-the-disappearance-of-judge-crater-and-the-new-york-he-left-behind

Skeptical Inquirer. (2023, May/June). Solving the disappearance of Judge Crater. https://pocketmags.com/us/skeptical-inquirer-magazine/mayjune-2023/articles/1307972/solving-the-disappearance-of-judge-crater

Smith, T. (n.d.). Last sighting of Judge Joseph Crater, 1930 (formerly Haas' Chophouse). The Clio. Retrieved July 25, 2025, from https://theclio.com/entry/128130

Stuff You Missed in History Class. (2018, September 17). The disappearance of Judge Joseph Force Crater [Audio podcast episode]. In Stuff You Missed in History Class. iHeart. https://www.iheart.com/podcast/105-stuff-you-missed-in-histor-21124503/episode/the-disappearance-of-judge-joseph-force-30207766/

TIME. (1931, September 14). STATES & CITIES: Lost Judge. https://time.com/archive/6745872/states-cities-lost-judge/

Tofel, R. J. (2004). Vanishing point: The disappearance of Judge Crater, and the New York he left behind. Ivan R. Dee.

Untapped New York. (n.d.). Today in history: The mysterious disappearance of Joseph Force Crater. Retrieved July 25, 2025, from https://www.untappedcities.com/joseph-force-crater/

Wikipedia. (2024, July 19). Hofstadter Committee. In Wikipedia. Retrieved July 25, 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hofstadter_Committee

Wikipedia. (2024, July 23). Joseph Force Crater. In Wikipedia. Retrieved July 25, 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Force_Crater

Wikipedia. (2024, July 11). Presumption of death. In Wikipedia. Retrieved July 25, 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Presumption_of_death

Wikipedia. (2024, May 22). Tammany Hall. In Wikipedia. Retrieved July 25, 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tammany_Hall

WikiTree. (n.d.-a). Joseph Force Crater (1889-1939). Retrieved July 25, 2025, from https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Crater-200

WikiTree. (n.d.-b). Stella Marie (Wheeler) Kunz (1887-). Retrieved July 25, 2025, from https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Wheeler-22809